| Trans | Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften | 16. Nr. | August 2006 | |

|

14.7. "Ränder der Welt" im Zeitalter transnationaler Prozesse |

||||

About the Inuit in Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat)

Astrid Zauner (Innsbruck)

Abstract

Until the beginning of the whaling age in the 17 th and 18 th century, the Greenlandic Inuit were more or less cut off from the achievements of the "western civilisation", and even then the modernisation progressed very slowly. Since the 1950ies, this development is terribly fast - almost like a journey with the time machine to the modern age. This time leap within one or two generations, connected with cultural uprooting, was too much for the majority of the local population and led to social problems such as alcoholism and an increasing suicide rate. Since two decades, more and more people fortunately stand up for their own country and traditions, their identification with their cultural goods and their self-consciousness increases again. This development is a big challenge, mainly for young citizens who try to define their own road between the traditional hunting culture of their ancestors and the modern lifestyle of today ...

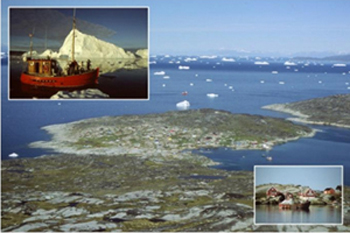

Greenland - in the local language "Kalaallit Nunaat", literally translated "the land of the people". About 57.000 people populate this huge country with a size of more than two million square kilometres. In theory, there would be about 38 km² for every person, but the major part (83%) of the island is covered with inland ice, so settlements are only found along the coastline. The Greenlandic population calls themselves "Inuit" which simply means "people". Most people think about "Eskimo" talking about people inhabiting arctic regions. When the Inuit migrated towards the north thousands of years ago, they got in contact with the American Indians - the Algonkin Indians called them "Eskimantsik" - "eaters of raw meat".

In Greenland’s history, seven waves of immigration are known: six Eskimo (starting about 2500 years BC) and one Norse (about 900 AC). Traces of these ancient Inuit cultures can be found all over the country, while Norse farming culture was limited to the southwest. The descendants of the Thule culture are the only ones surviving; they’re the ancestors of today’s population.

The distance between West Alaska and East Greenland is more than 9000 km. Inuit have always been a hunting society, following their prey. In the huge area, many small tribes have developed - characteristic for all of them is the spatial isolation and the perfect adaptation to the prevailing environment. They’ve all got the same roots, but their lifestyle, their hunting technology, their mythology and their language showed a slightly different development. The base of the language is the same, but the dialects are very different. For a person from West Greenland, it’s easier to understand a Canadian Inuit than an East Greenlandic one.

The distance between West Alaska and East Greenland is more than 9000 km. Inuit have always been a hunting society, following their prey. In the huge area, many small tribes have developed - characteristic for all of them is the spatial isolation and the perfect adaptation to the prevailing environment. They’ve all got the same roots, but their lifestyle, their hunting technology, their mythology and their language showed a slightly different development. The base of the language is the same, but the dialects are very different. For a person from West Greenland, it’s easier to understand a Canadian Inuit than an East Greenlandic one.

The first Europeans coming to Greenland were the Vikings. 875 an Icelandic vessel was blown towards the east cost of Greenland and when the sailors returned, they reported about the new land in the west. For the Norwegian outlaw Eiríkur Thorvaldson (Eric the Red), who was living in Iceland, this was the chance for a new life. He was convicted of murder again and rather than remain a persona non grata, he decided to leave Iceland and went to Greenland. When he came back, he told the people about the "green land" and finally loaded 25 ships with prospective colonists including their animals. Only 14 ships arrived, but at their peak, the Norse settlements included some 300 farms and around 5000 inhabitants. These farmers living in South Greenland never had much contact to the Inuit hunting society living further north. In 1261 Greenland was annexed by Norway and a trade monopoly was imposed. The agreement was that two ships would visit South Greenland annually with supplies and carry locally-made goods back to Europe. In 1397, Denmark, Norway and Sweden were united and Norwegian’s North-Atlantic-relations went to Denmark. Unfortunately the climate became worse and the sea ice and political unrests in Europe became more abundant, so the connection was interrupted. In the 15 th century, the Norse disappeared without a trace.

In the late 16 th century, speculations about a possible North-West Passage, linking Europe with the far West, were an important political feature. Many countries sent expeditions towards the north to find this sea route. Seeking for the North-West Passage, whaling nations discovered the rich waters of the Arctic and in the 17 th and 18 th century, up to 10.000 men arrived annually on Danish, Norwegian, British, Dutch, German and Spanish whaling vessels. The whalers were trading with the Inuit and the locals got to know modern weapons, glass, pearls and alcohol and soon became dependent on these modern goods wich they didn’t even know before.

1721 the Danish-Norwegian missionary Hans Egede came to Greenland to convert the Norse to Protestantism. As he couldn’t find them, he decided, that the Inuit souls were also valuable. In the following years, many missions were set up, usually together with trading posts. Before, the Inuit believed in the living nature and shamanism was an important part of their life - now this tradition with e.g. drum and mask dances was forbidden and little by little the Inuit became more and more dependent on their colonial country. Finally Denmark imposed a trade monopoly which allowed trade only with Denmark.

1953 Greenland became an equal county of Denmark and Greenlanders acquired full Danish citizenship. 1979 the island obtains self-administration and is now "a separate nation within the Danish kingdom".

With the time, also the type of accommodation changed. Many people think about "igloo" as the typical type of accommodation - and it is, but "ichlu" just means "house" in the Inuit language. All Inuit tribes had to adapt to the prevailing environment and materials. Some always had to follow their prey, so they lived in tents, others - like the ones in Greenland, mainly lived in huts made of peat and stones and only used tents on their hunting journeys. Snow igloos were only built during hunting journeys or as guest houses. The whalers finally brought wood and glass to Greenland, so the walls were often made of planks. With the time, the style was more and more adapted to the Scandinavian one, and nowadays, prefabricated buildings are imported from Denmark or Norway.

As mentioned before, Greenland became an equal county of Denmark in 1953. Equal also means, that the Greenlandic people obtained the same rights as the Danish citizens, such as education and social health service. But how to guarantee that on an island with more than 2 Million km² and settlements which are situated 100 km away from each other? The only possible solution seemed to gather the people in the bigger cities (G-60 plan). Schools, hospitals, factories and blocks of flats were built. This concentration took place within about 10 years - within one generation many of the Inuit changed their traditional with a modern life.

As mentioned before, Greenland became an equal county of Denmark in 1953. Equal also means, that the Greenlandic people obtained the same rights as the Danish citizens, such as education and social health service. But how to guarantee that on an island with more than 2 Million km² and settlements which are situated 100 km away from each other? The only possible solution seemed to gather the people in the bigger cities (G-60 plan). Schools, hospitals, factories and blocks of flats were built. This concentration took place within about 10 years - within one generation many of the Inuit changed their traditional with a modern life.

Before, their rhythm was planned by nature, now by the clock of a factory.

Before a good hunter was a respected person, now a good factory worker was.

And where to put all the hunting equipment, where all the dogs you need for a dogsledge, were the hunted prey?

The change was too sudden for many of them - they lost their roots - many committed suicide, many became addicted to alcohol ...

An even worse example happened in Thule, in the North of Greenland. When Denmark was occupied by Germany during the second word war, it was not able to care for Greenland’s supply any more. The USA got the right to build air bases in Greenland, if they take over the supply of the island. Except the Thule Air Base, all of them are closed today. When the Air Base was built, thousands of soldiers came with planes and vessels to the remote area. Due to the noise, the hunting conditions became worse, but the Inuit decided to stay. In 1953 the Americans wanted to expand their territory and the Greenlandic settlement was in their way. They suggested them to build a new settlement for them, more than 100 km further north. As the hunting conditions were even worse there, the locals didn’t want to go. Finally, they were convinced by the threat that bulldozers would flatten their houses if they wouldn’t move voluntarily. Finally they left.

The living conditions and the infrastructure were much better in Qaanaaq, their new home town - the houses had running water, there were roads, a nursery station, a school and so on - but they were a traditional hunting community, so what to do with all these modern achievements? Some people still start crying if they’re talking about these times ...

"Is it okay to get plastered if you’ve got children? Where are the limits?"

Nowadays there are many campaigns against alcohol and violence - and it became much better within the last decade.

Fortunately, many settlements managed to handle the problem with alcohol and suicide. Some settlements even decided not to sell alcohol in their local shop.  Although you can buy alcohol in Rodebay, you hardly see any drunken people, except when there’s a big party. Rodebay has discovered tourism. A German couple runs a restaurant with Greenlandic specialities there - buying the meat from local hunters and asking local skippers to do transfers and excursions for the tourists. The settlement with 42 inhabitants is close to one of the tourism centres of Greenland - a chance for them. Many Danish, and some German people have chosen Greenland as their home, most of them work in tourism there. Unfortunately there are not many locals yet who have got the language and economical skills to run the business - but they’re learning by watching and doing ... . Tourism is one of the growing economical sectors in Greenland.

Although you can buy alcohol in Rodebay, you hardly see any drunken people, except when there’s a big party. Rodebay has discovered tourism. A German couple runs a restaurant with Greenlandic specialities there - buying the meat from local hunters and asking local skippers to do transfers and excursions for the tourists. The settlement with 42 inhabitants is close to one of the tourism centres of Greenland - a chance for them. Many Danish, and some German people have chosen Greenland as their home, most of them work in tourism there. Unfortunately there are not many locals yet who have got the language and economical skills to run the business - but they’re learning by watching and doing ... . Tourism is one of the growing economical sectors in Greenland.

... but how to travel as a tourist, as a local? There are no roads connecting settlements with each other. For short distances, up to 150 km, the locals use their own motor boats - for them it’s like the car for us. For bigger distances the ferry is used, but the vessel only runs between the cities in the south and the middle west coast - and only during summer. In the last decade, airports have been built in most cities and many settlements can be reached by helicopter. In winter, most people still prefer the dogsledge for hunting and spare time excursions. The snow scooter is the faster choice - but were to refuel it in the middle of nowhere? A team of about 8-12 dogs which you need for a sledge needs one seal per day which you can hunt easily on your way.

Hunting and fishing has always been the most important income for Greenland and it’s still the main economic factor. While shrimps, cod and halibut are mainly caught to be exported, seals and whales are for local use only. In the big cities - big means between 1000 and 6000 inhabitants - only a few people still live from hunting and sell their prey at the local market. Most people enjoy the easy way of buying food in the supermarket.

Further north and in the east, where a constant supply of the small local shops can’t be guaranteed and where there are almost no other job opportunities, many people are still dependent on hunting. Some of them have found a perfect coincidence in traditional and modern life. While Equilatoq is working on the seal, her husband J ø rgen checks the internet for the weather forecast for his next hunting excursion.

Greenland has always been a hunting community and seals have always been hunted. For many local town-dwellers hunting is only a hobby any more - one of the few possibilities of passing time - or a possibility to safe money. It’s much cheaper to shoot a seal on a weekend excursion than to buy beef or pork in the shop - and it tastes better, and fresher. Some of you might think - "If they can buy their food, why do they still hunt wildlife?" On the other hand - is it better to breed masses of cattle and pigs in tiny stables, animals which have never seen the sun, which could never enjoy an appropriate life?

For thousands of years, Inuit were hunting and have not much affected wildlife. When the whalers came, masses of whales were slaughtered; using big vessels it was much easier for them than for the Inuit with their kajaks. Nowadays, thanks to the better health system, the Greenlanders become older and more children survive than in earlier days, as life is not that hard any more. The Greenlandic population is growing and the ways of hunting have changed by using new weapons. On the other hand, the sensitive arctic ecosystem suffers from global warming, the ocean currents change their temperatures, the period of frozen sea ice is shorter. Many animals change their migration routes; others suffer from a serious decrease in abundance. The major threat for a polar bear, for example, is not the Inuit hunter, but the shortening of its prosperous hunting period - for a polar bear it’s the easiest way to catch seals in their breathing holes in the sea ice.

These influences make it inevitable to react and act. Some animals, like humpback whales, are strictly protected. Others, like belugas and narwhales may only be hunted in the traditional way, with kajak and harpoon. Also polar bears may only be hunted by professional hunters. The Greenlandic Homerule Government already sets annual quota for many species such as reindeer, musk ox, salmon and several whale species. A big challenge is the education of the local hunters. Especially in schools, but also during public meetings, public relations work is done. It’s never too late ... .

You got the impression that, for a Greenlander, the favourite way of passing time is hunting? Well, for many of them it is indeed, as there are not many other possibilities. In the short summer, everyone loves to do excursions, combined with a fine barbecue with seal or fish soup and some fresh berries. To maintain and revive tradition, kajak clubs were found - young people can build their own kajak and exercise with it - some of them participate at international championships where they are usually very good. Nevertheless - the Greenlandic national sport is football - there are hardly any settlements without a football square!

To maintain and revive tradition, many settlements have drum or mask dance festivals and of course a choir. Mask and drum dance was an important way of solving problems in the past, when shamanism was still a part of their lives.

Handicraft is not just a hobby - many people who couldn’t get appropriate school education in their youth, get the chance to earn some money with spinning, sewing and carving. Nowadays it might be "only art", then it was essential for survival.

Education is free in Greenland; in all the cities and most of the settlements, there are primary schools. Since some years, Greenlandic is the administrative language, so pupils are only taught Greenlandic in the first few years. By the end of the primary school, they start to learn Danish, and much later English. School attendance is compulsory for nine years - to attend a high school, the children have to move to bigger cities within Greenland or, if they want a better education, they go to Denmark. Greenland has got a small university in the capital Nuuk, but most students go abroad to study in Denmark, Canada or the USA.

The education of the indigenous youth is of high importance, as education is one of the major keys to the stony road to independence and self-determination. Unfortunately, the drop out rate of young Inuit is enormous. Young people give up because of mental health problems, because they do not master the colonial language, because of homesickness or because the education systems work so differently from their own culture. A major target of all Inuit societies and political plans is to offer specific cultural help to empower the youth who stands between two realities.

"In my opinion, we must deliver the best education possible by taking the best parts of our own traditional systems with what the outside world would have to offer." (Aqqaluk Lynge, president of the ICC 1998)

The Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ІСС) is the international organization representing approximately 150.000 Inuit living in the arctic regions of Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Chukotka, Russia.

The principal goals are:

to strengthen unity among Inuit of the circumpolar region

to promote Inuit rights and interests on the international level

to ensure and further develop Inuit culture and society for both the present and future generations

to seek full and active participation in the political, economic, and social development in our homelands

to develop and encourage long-term policies which safeguard the arctic environment

to work for international recognition of the human rights of all indigenous peoples

Further targets of the ICC is the promotion of a student exchange programme and a hunters’ and fishermen’s education programme.

© Astrid Zauner (Innsbruck)

REFERENCES

Adler, Christian (1981): Der letzte Sieg des Zauberers. Abenteuer und Beobachtungen bei Naturvölkern. Umschau. Frankfurt. p. 7-82

Barth, Sabine (2001): Grönland, DuMont-Reisetaschenbuch, DuMont Buchverlag Köln

Berthelsen, Christian, Mortensen, Inger-Holbech & Mortensen, Ebbe (1993): Kalaallit Nunaat Greenland Atlas, Nuuk, 127 pp.

Cornwallis, Graeme (2001): Iceland, Greenland & the Faroe Islands. The ultimate chill-out destination, Lonely Planet Publications, Melbourne, Oakland, London, Paris, 640 pp.

Génsbøl, Benny (1999): Naturguide til Grønland. Gads Forlag, København, 448 pp.

Hertling, Birgitte (1993): Greenlandic for travelers. Atuakkiorfik, Nuuk, 61 pp.

Jakobsen, Bjarne Holm et al. (2000): Topografisk Atlas Grønland. Atlas over Danmark Serie II Bind 6. Det Kongelige Danske Geografiske Selskab og Kort & Matrikelstyrelsen. C.A. Reitzels Forlag. København

Knudsen, Thorkild & Baunbæk, Lene (2003): Greenland in figures 2003 (2.Edition), Statistics Greenland, Greenland Home Rule Government; www.statgreen.gl

Martens, Gunnar et al (2003): Peary Land. At tænke sig til Peary Land - og komme der. Atuagkat, Nuuk, 332 pp.

Mary-Rousselière, Guy (2002): Qillarsuaq. Bericht über eine arktische Völkerwanderung. Atuagkat, 206 pp.

Penz, Franz (2004): Angakoq. Seelenführer im ewigen Eis (Spiritualität der zirkumpolaren Völker), Innsbruck, 35 pp.

Petersen, H.C. et al (1991): Grønlændernes Historie fra urtiden til 1925. Attuakkiorfik, Nuuk, 273 pp.

Schmidt Mikkelsen, Peter et al (2001): Nordøst-Grønland 1908-60. Fangstmandsperioden. Aschehough, 423 pp.

Walsøe, Per (2003): Goodbye Thule. The compulsary relocation in 1953. Tiderne Skifter, Viborg, 258 pp.

Qilalugaq Qernertaq pillugu paasissutissat. Fakta om Narhval (2004). Tulugaq. Grønlands Hjemmestyre, Nuuk, 15 pp.

Vi skal passe på fangstdyrene - en pjece til børn om bæredygtig udnyttelse. Tulugaq. Grønlands Hjemmestyre, Nuuk, 15 pp.

14.7. "Ränder der Welt" im Zeitalter transnationaler Prozesse

Sektionsgruppen | Section Groups | Groupes de sections

![]() Inhalt | Table of Contents | Contenu 16 Nr.

Inhalt | Table of Contents | Contenu 16 Nr.