Sektionsleiter | Section Chair: T. Brian Mooney (Singapore Management University)

| Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften | 17. Nr. | Juni 2010 | |

| Sektion 8.20. | Rationality, Ethical Incommensurability and Existential Communication Sektionsleiter | Section Chair: T. Brian Mooney (Singapore Management University) |

||

Social Virtues Within and Across Cultures

Against the Idea of Universal Rationality

Mark Nowacki (Singapore Management University) [BIO]

Email: nowacki@smu.edu.sg

I. Introduction

Human beings appear endlessly creative in their ability to develop distinct yet viable forms of social organization. Each form of viable social organization embodies a distinct way of life and valorizes the particular, and sometimes peculiar, social virtues that support it. Given the bewildering variety of viable human societies, one might expect to see a similarly bewildering variety of virtues exhibited by individuals living within these diverse societies. And we do indeed encounter variety – but far less than we might expect.

Originally proposed by the eminent anthropologist Mary Douglas, Cultural Theory (CT) is a conceptually rich and empirically well-grounded theory in the social sciences. A distinctive feature of CT is its insistence that there are only five basic types of social organization ("ways of life") to be found in any viable society.(1) Proponents of CT also point to a requisite variety condition: within any sufficiently large viable society these five ways of life are mutually supporting and mutually interdependent. (Of course, within a given society one way of life may be relatively more prominent than another.)

The five ways of life identified by CT are themselves correlated with distinct "forms of rationality," i.e., coherent yet incommensurable schemes for understanding the world. Adherents of a particular form of rationality behave in accordance with their rational interpretation of the world, and in so doing (I argue) develop specific virtues to support successful performance of those actions that are in keeping with their way of life.

To illuminate the epistemological structure of the forms of reasoning and characteristic virtues and virtuous behaviors embedded within the identified five ways of life, I draw upon G.E.M. Anscombe's brief yet suggestive work on connatural knowledge.(2) The key insight that grounds the notion of connatural knowledge is that possessing a certain nature orients a knower to recognize and understand those things that are in accord with that nature. When applied to the virtues – which, as Aristotle notes, constitute a second nature within us – connatural knowledge emerges as an inclination to recognize those particular actions that are consistent with a specific virtue the knower possesses and reject or fail to recognize those actions that are not in accord with the possessed virtue.

I argue that conjoining these three rich conceptual schemes – CT, virtue ethics, and connatural knowledge – results in substantial theoretical payoffs for both social scientists and philosophers. For instance, the proposed conjunction permits more precise understanding and characterization of distinct types of moral personality and forms of moral reasoning. The proposed conjunction also casts considerable light on important puzzles in virtue ethics, including the traditionally vexed question of the unity of the virtues. By elevating forms of ethical reasoning to the level of social facts, it becomes possible to make empirically well-grounded normative recommendations on what sorts of perspectives and considerations ought to be brought into play to arrive at more robust social policies. Finally, the proposed conjunction can aid efforts to promote ethical understanding both between distinct ways of life found within a single society and among diverse ways of life located across different societies.

In section II below, I present an outline of what may be considered mainstream CT.(3) Section III marks a transition from CT to virtue ethics. Section IV applies the concept of connatural knowledge to the forms of virtuous behavior characteristic of different ways of life. Section V spells out a range of possible benefits that bringing these three theoretical schemes together may have for the social sciences and philosophy.

II. Presentation of Cultural Theory

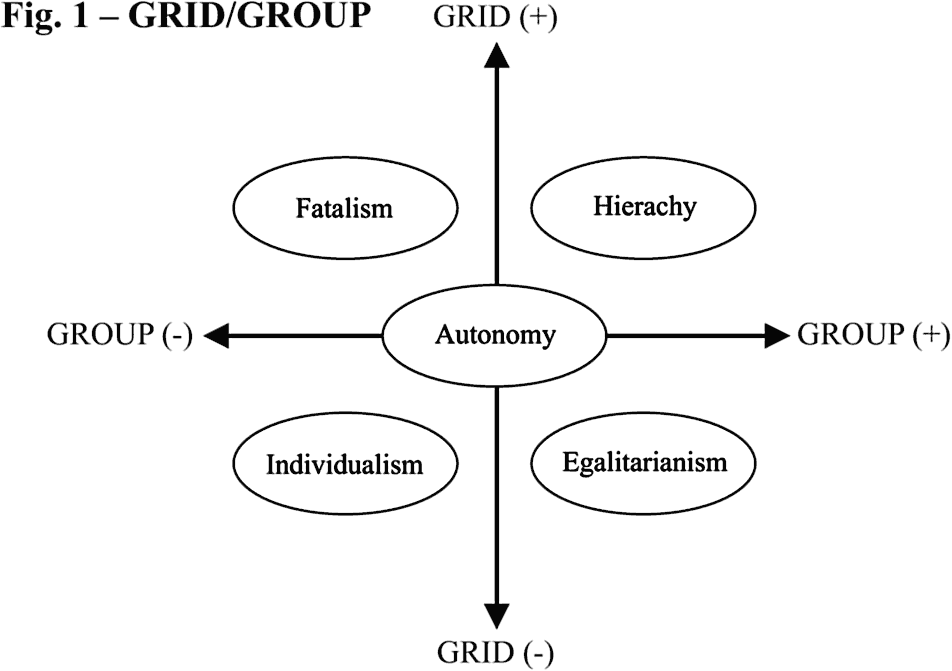

Mary Douglas argues that variability in an individual's social involvement can be captured by appealing to two different dimensions of sociality: grid and group. Grid measures the degree to which an individual is bound by externally imposed prescriptions. Group measures the degree to which an individual is absorbed into bounded social units. The greater the group, the more an agent's choices are bound by group decisions. The greater the grid, the less an agent's actions are open to individual negotiation.

Graphically, this resolves into the picture given in Figure 1 above. The five ways of life described within CT include:

The first four ways of life are all socially engaged and are differentiated by the means whereby they seek to maximize social transactions. Hermits, about whom I will have little to say in this paper, withdraw from all forms of coercive or manipulative social control. In doing so they effectively remove themselves from the social map. (It is, in fact, common for practitioners working within CT to leave out the Hermit's way of life and focus exclusively upon the four engaged forms of life.) St. Anthony living in the desert would be a typical example; in literature we have Mac and the Boys from Cannery Row. Given this paper's focus on the social virtues, I will be more concerned with the four socially engaged ways of life.

Members of the Singapore civil service score high on both grid and group and hence constitute examples of Hierarchists. The members of several utopian communities (e.g., the Walden Two inspired Twin Oaks community in Virginia), and certain branches of the Green Party, constitute clear examples of Egalitarians. Self-aggrandizing, self-made capitalists who splash their way across the daily papers – here I have in mind people like Donald Trump, Bill Gates, and the unlamented Ivan Boesky – are examples of Individualists. Non-unionized graduate students, who are notoriously vulnerable to the hot-and-cold winds of fate blown by capricious professors, inhabit the Fatalist quadrant. (I believe we call these unfortunate souls ABDs.)

What Hierarchist civil servants and Egalitarian utopians have in common is a strong sense of group identity. Decisions made by civil servants are taken to be binding on civil servants just as votes taken in Twin Oaks are seen as binding on all Twin Oaks members. Where Hierarchists and Egalitarians part company, however, is along the grid dimension. Modes of interaction among meritocratically-distinguished group levels within the Singapore civil service are heavily circumscribed and communication is heavily filtered through formally-codified official channels. It is, for instance, more unthinkable for a junior civil servant to approach a Minister or Member of Parliament than it is for a simple member of the public. By contrast, Twin Oaks members experience extremely fluid intra-group social relations that embody their notion of institutional equality. To speak the sociologist lingo for a moment, both Egalitarians and Hierarchists maximize their group social transactions, but Egalitarians do so by keeping their group apart from other groups (and hence increase intra-group transactions) whereas Hierarchists maximize transactions by organizing their group into ranked relations with other groups (hence promoting systematic inter-group transactions).

Individualists and Fatalists likewise maximize their social transactions, but do so along social networks without entering into bounded groups. Both Individualists and Fatalists behave like social atoms bounding and re-bounding within a thinly-disguised Hobbesian state of nature, where collisions between atoms represent contacts or nodes within social networks. The difference between these two ways of life turns largely upon the approach to these atomistic collisions. Network centrists, like the free-wheeling Individualist captains of industry, are intent on maximizing their network reach and power. The non-unionized slave labor we call graduate students combine an atomistic one-to-one relation with their exploiting professor with a heavily prescribed existence wherein what they must do to please their masters is finely regulated – what to teach, when to teach it, how to grade it, what to research, when to research, how to research. These are all the effusions of a malevolent environment over which the Fatalist has little or no control.

Each of the five ways of life identified by CT has a correlated form of rationality that upholds and supports it. These forms of rationality are defined by the manners in which members of discrete ways of life justify their social relations both to themselves and to others.(4) For philosophers, the notion of forms of rationality will certainly recall the theory of tradition-bound discourse advanced by Alasdair MacIntyre in Whose Justice? Which Rationality? While I would not go quite as far as MacIntyre, there is much truth in his position that "there is no standing ground, no place for enquiry, no way to engage in the practices of advancing, evaluating, accepting, and rejecting reasoned argument apart from that which is provided by some particular tradition or other."(5)

Without attempting to spell out the fundamental rational principles adopted within each form of rationality – that is a massive empirical project for another day – it would be beneficial to consider a specific case of how different, socially embedded assumptions are in fact deployed to rationally justify claims and positions within different ways of life. A suggestive example is introduced by the authors of Cultural Theory with respect to the divergent "Myths of Nature" that underlie the approaches that different groups take when managing ecosystems. A graphical representation of these myths is given in Figure 2 below.(6)

I will briefly unpack what these pictures mean. I will not attempt to defend these CT-based interpretations (that work has already been done elsewhere(7)), but instead will trust that the truth within the descriptions will sufficiently resonate with the reader's experience.

Let us start with the Individualist. For an Individualist, Nature is benign and bountiful. There are no limits to Nature's fecundity. Nature's resilience ensures that, whatever environmental shocks may be encountered, Nature will always overcome them. Nature is to be exploited for humanity's benefit.

For an Egalitarian, Nature is ephemeral. The least shock can have disastrous results from which fragile Nature never recovers. In these circumstances Egalitarians may come to see human beings as an intrusion or parasite. We are to tread lightly, if at all, upon the Natural order.

Hierarchists see Nature as bountiful within limits but vulnerable to extreme shocks. Prediction, control, and careful management of environmental resources is the Hierarchist's reaction to Nature. Large-scale projects, involving the advice of experts, are the norm.

Finally, the Fatalist sees Nature as inherently capricious. The least push results in random and unpredictable movement across the plain. Fatalists do not happen to Nature so much as Nature happens to them. Fatalists see themselves as the inevitable victims of an environment over which they have little or no control.

Prudence dictates this suffice as an introduction to Cultural Theory. It is not my task here to justify the adequacy and wide-scale applicability of CT. I need only remark that CT has been empirically successful in explicating a variety of world cultures and has been applied to everything from environmental policies and Kondratiev waves to Everest expeditions, the literary preferences of Benjamin Disraeli, and Aristotle's four causes.(8) Cultural Theory has the great merit of being a general analytic tool that can be used to examine diverse peoples, cultures, and forms of political organization. CT also has the merit of generating propositions that are empirically testable and in-principle falsifiable.

III. From Cultural Theory to Virtue Ethics

At this point, I would like to transition from the forms of rationality used to justify different ways of life to a more focused discussion of the standards of rationality employed in making normative judgments within those ways of life. There are here two broad questions to be addressed. The first question is whether employing CT is for systematic investigation of ethical matters. The second question is this: presupposing a positive answer to the first question, how is CT useful for ethics? In this section I will lay out some reasons for returning an affirmative response to the first question, and in the subsequent section of the paper I will make some suggestions about how CT can be both concretely and fruitfully employed.

It is clear that various proponents of CT do believe that their approach has connections to normative ethics. In the midst of a discussion of how an individual's being embedded within a particular way of life impacts the manner in which that individual approaches questions involving the reconciliation of needs and resources, Thompson et al. write:

It is not the physical but the moral constraints, the availability of reasons acceptable to others for adopting and sustaining a strategy, that limits and shapes our strategies for making ends meetâ¦.Supporters of each way of life construct their ends to make their cultural biases meet up with their preferred pattern of social relations. Their strategies do what is most important to them – uphold their way of life.(9)

A more general argument for why we should expect CT to have a place in ethical discourse runs as follows. Ethics as the study of what humans should do is concerned with guiding human actions and making apt choices. But choice-worthy objects are always judged with respect to what is better or best for us to do. Judging in the light of what is better or best implies that some sort of evaluative standard is being employed.

From an empirical standpoint, what sort of evaluative standard do we use? One plausible answer, advanced by virtue ethicists, is that the ethical standards we use are those into which we have been habituated. Through experience and education human beings are indoctrinated into the virtues. Virtues, as Aristotle teaches us, are deliberated, stable dispositions (i.e., habits), based on a standard that we apply to ourselves, and defined by reference to the practical reason displayed in the actions of the euphronimos (i.e., man of practical wisdom).(10) In a more contemporary idiom, virtues are embodied heuristics, rules of thumb guiding effective practical action that have been coded into their human subjects via a process of training and reflective appropriation.

Virtues run deep. As Aristotle suggestively puts it, virtues form a second nature within us. Virtues are tools of human flourishing,(11) making their possessor good and rendering good his work.(12)

Virtues allow their possessors to make appropriate and effective choices within the practical sphere even in the absence of formal deliberation. They do so by inclining the virtuous individual both to perform actions of a certain type and to develop the sort of character that will be a font of actions of this desired type. The thematic nature of actions that virtuous individuals undertake can thus be seen as supportive of a particular way of life.(13) A just individual is inclined to just acts, and a courageous individual is inclined to courageous acts. The virtues we possess prompt us to move in productive grooves, and that's a good thing.

It is my position then that each way of life identified by CT comes packaged with an internally coherent set of virtues that render reasonable and support the central goals of each way of life. As the proponents of CT point out, each way of life is constrained with respect to its viability, its guiding metaphysical vision of what the world is like, and what it takes nature, both physical and human, to consist in. The coherence of the set of virtues possessed by any individual is constantly tested against that socially-embedded individual's understanding of the world. Reinforcement comes in the form of both positive and negative social feedback. As John Dewey argues:

Honesty, chastity, malice, peevishness, courage, triviality, industry, irresponsibility are not private possessions of a person. They are working adaptations of personal capacities with environing forces. All virtues and vices are habits which incorporate objective forces. They are interactions of elements contributed by the make-up of an individual with elements supplied by the out-door world. They can be studied as objectively as physiological functions, and they can be modified by change of either personal or social elements.⦠But since habits involve the support of environing conditions, a society or some specific group of fellow-men, is always accessory before and after the fact. Some activity proceeds from a man; then it sets up reactions in the surroundings. Others approve, disapprove, protest, encourage, share and resist. Even letting a man alone is a definite response. Envy, admiration and imitation are complicities. Neutrality is non-existent. Conduct is always shared; this is the difference between it and a physiological process. It is not an ethical "ought" that conduct should be social. It is social, whether bad or good.(14)

There is, then, an inherently social dimension to the virtues. Insofar as particular kinds of act are valued by a group, the group will habituate its members in those virtues that lead to performance of valorized acts. And what sorts of acts will be valorized by a group? Clearly, those sorts of acts to which the virtues possessed by group members incline them.

There is bound to be much overlap in the list of virtues recognized within each of the five ways of life CT identifies. This is hardly surprising: ways of life are constrained by their viability, and these are five ways of organizing social relations that have proven effective time and time again. Securing food, clothing, and shelter, child rearing, education, and collective decision-making, must be present in any viable form of social organization; hence, there will always be demand for inculcating social virtues ordered to and supportive of these basic necessities. Moreover, at least the four socially-engaged ways of life – the Individualist, the Fatalist, the Hierarchist, and the Egalitarian – will all be found in varying proportions in any long-term stable society.(15) Since collective decision-making is necessary for any viable human society, at a very minimum the functional requirements of effective communication will necessitate that there be some areas of overlap in concern and approach among the four ways of life.

What certainly does vary from one way of life to another are the relative emphases placed upon specific virtues. For instance, Individualists are likely to include the notion of risk-taking as a key component of their self-understanding. The virtue of courage is then likely to be valorized. Bill Gates and Donald Trump identify themselves as the sort of people who make one bold business move after another, and are appropriately rewarded by the market for their courage in the face of risk. Fatalists, on the other hand, cherish the virtue of patience. If good things don't come to those who wait, at least those who wait are still around in the future when good things might come. Hierarchists cherish group loyalty and incorporate formal recognition strategies that encourage members to develop a keen sense of propriety and group-oriented responsibility. Egalitarians, at least within their group, adhere to a strong sense of human dignity and display a keenly-honed sense of fair and equal play. Last but not least, Hermits are the virtuous converse of those cynics whom Oscar Wilde derided for knowing "the price of everything and the value of nothing." Living their lives in autonomous self-reliance, hermits are reputed to know the value of everything and the price of nothing.

So, pulling back a bit, there seem to be good prima facie reasons for suspecting that the study of ethics can be illuminated by consideration of the five ways of life identified by CT. Finally, if anecdotal evidence be admitted to have some weight, I would like to share one last bit of empirical evidence for the potential usefulness of bringing CT-derived considerations into the discussion of ethics.

Among other sordid activities I have been known to engage in, I occasionally visit elementary schools to talk with children about philosophy. This is my nod to Socrates, taking his status as a "corrupter of the youth" to its logical extreme. In a number of sessions that I have conducted with very young children – kindergarteners and lower-primary students mostly – I have run variations on the following experiment.

I begin by having the children sit in a circle on the floor. After joining them, I begin asking them questions. Whenever a child volunteers an answer to a question, I give them an encouraging response and also a small colored card. I keep doing this for some time, and after a while some children have collected a number of the colored cards, others have collected a few cards, and some children, because they did not answer any questions, have no cards at all.

Now for the moment that makes it all worthwhile: I reach behind myself and pull out a large bag of candy. Every child is awarded as many pieces of candy as they have cards. Shock all around: nobody saw this coming. The children explode: "It's not fair!" – "Yes, it is!" – "No it isn't!" – chaos ensues.

What happens next is as wonderful as it is predictable. The kids start arguing. Not in the sense of fisticuffs, but in the sense of advancing reasons in support of conclusions. They are surprisingly good at formulating relevant principles and using those principles in sharing their views with one another. My uniform experience, in the different countries on different continents where I have run this experiment – is that even quite young children expect to offer reasons for behavior and to have their reasons looked at and understood by other people.

Now to go into the reactions of the children in more detail. What sort of reasons do the children offer? Here is a perfectly typical sample:

Whatever else justice might be, it is a virtue. In the present case, the children's dispute concerns how we should formulate and then apply the appropriate principle of distributive justice.(16) What makes for a just distribution of candy? I don't know. But then again, I'm not too sure about what makes for a just distribution of goods in society generally. What I do find interesting, though, is that every time I have run this experiment, I have been able without any strain to map the children's responses onto the ways of life described by CT.

IV. Connatural Knowledge and the Virtues

Thus far I have been discussing CT's grid/group typology, the different ways of life, and the forms of rationality that support different ways of life. I have also suggested that virtues are in some way related to, and perhaps expressions of, forms of practical rationality correlated with distinct ways of life. I would now like to advance the discussion another step by taking up Elizabeth Anscombe's suggestion that connatural knowledge provides the appropriate model for the kind of knowing that is at play in the exercise of virtue. I argue that the type of knowing characteristic of ethically engaged individuals displays features that not only support the empirical findings of CT but also open up interesting vistas for philosophers concerned to give an empirical grounding for their normative suggestions. Moreover, traditional puzzles within ethics, specifically the puzzle regarding the unity of virtues, can now be given empirically well-grounded, if yet still tentative, answer.

According to Anscombe, connatural knowledge is knowledge that is readily known by beings of a certain nature. A metaphysical example would be this: since human beings are embodied intelligences, it is connatural for humans to know material beings. Humans thus differ from angels who, as immaterial beings, connaturally know immaterial objects.

In ordinary discourse, appeals to connatural knowledge appear in phrases of the form "I know what it is like to..." So, for instance, we know what it is like to be writing well or speaking well. We know what it is like to be a stranger in a country and not know its language or customs. Or again, to use Anscombe's example: "I know what it is like to find my topic running into the sand, or running away with one in an unintended direction like a badly-trained horse."(17)

Since, as Aristotle notes, the virtue of a virtuous person is like a second nature, there are instances of knowing correlated with this second nature and hence connatural to a virtuous individual. In particular, within a virtuous individual there will arise a capacity to recognize what actions accord with and which actions are contrary to the virtue. For instance, a generous individual is likely to avoid or reject certain courses of action because those actions are, without any difficulty, perceived to be ungenerous. Furthermore, performing certain kinds of action simply will not occur to a generous person as a live possibility. If someone were to suggest such and action, a generous individual would quickly brush aside the suggestion. The connatural knowledge of a generous individual thus includes an inclination not only to perceive certain choices in either a generous or ungenerous light, but also an inclination to perform generous acts and shun ungenerous ones. Granted, a vicious individual possessed of certain sharpness or cleverness may be able to recognize various actions as generous or ungenerous yet still lack the virtue of generosity. But, this vicious person will feel no inclination to pursue the generous act or shun the ungenerous one.(18)

The connatural knowledge of the virtuous is cultivated through a process of habituation. This process starts early in our human life, as evidenced by my class of kindergarteners who, without careful reflective judgment, could immediately pronounce my distribution of candy as unfair.

Reflection on the kind of knowing made possible through connatural knowledge permits me to make an interesting side observation. Anscombe calls our attention to the phenomenon of "affected ignorance". We very often do not want to know things that force us to reconsider our fundamental assumptions. In fact, even simple facts often have great difficulty penetrating our awareness if they are the sort of things that would show up our own opinions in a bad light. It is frequently said that the homeless are invisible. And this is literally true. To recognize that somebody is cold or hungry is a simple observation, but it is an observation that would probably not be made unless someone is inclined to or interested in helping those who are cold and hungry.(19)

V. Cui Bono?

What profit lies in bringing the notion of connatural knowledge into conjunction with an understanding of virtues as embedded in and supportive of ways of life? I foresee at least one advantage considered purely from the standpoint of social scientists, one shared advantage from the combined perspective of social scientists and philosophers, and two distinct advantages from the standpoint of philosophers.

First, from the standpoint of social science, there is a widely held yet mistaken view that normative considerations are outside the proper purview of the social scientist. The roots of this opinion, I suspect, have something to do with entirely understandable worries over importing non-objective considerations into the positive sciences. One does not, as a scientist, want bias to cloud one's judgment. Shouldn't one let objective facts speak for themselves?

In response, it may be noted that we have come too far, and grown too old, in our understanding of the history and philosophy of science to hold so naïve a position any longer. Thomas Kuhn has taught us that facts do not speak for themselves but require context and paradigms of interpretation. By conjoining the descriptive power of the notion of connatural knowledge with the explanatory hypothesis that there exist normative claims embedded within distinct ways of life, social scientists are in a position to elevate what are basically psychological facts grounded in human nature to the level of social facts. As social facts, items that are known connaturally can assume their proper place within the social sciences, as for instance, in functionalist approaches to sociology descended from Max Weber. These newly-recognized social facts can be integrated into anthological and sociological studies of institutional forgetting and remembering, such as that found in Mary Douglas' How Institutions Think.

A common advantage shared by social scientists and philosophers is the transdisciplinary field of study that emerges. Considered as social facts, controlled observation of what is connaturally through adherence to a way of life opens up a new field ripe for investigation by social psychologists, sociologists, students of organizational behavior, social philosophers, and ethicists.

For philosophers, the anthropological grounding of CT and the replication of the five forms of life across viable human cultures helps explain why there is less variation in basic ethical propositions across cultures than the cultural relativists have led us to expect. Viability constrains social possibility – this is not a particularly novel idea. But the CT requisite variety condition is novel. On the one hand, the requisite variety condition explains the de facto presence of ethical diversity rightly noted by cultural relativists. Different groups of people do indeed set some of their ethical priorities differently, and viable human societies need that kind of diversity. But the distinctness and limited quantity of viable forms of human sociability described by CT constrains the wild growth of the relativist program. We are, ultimately, led to a constrained relativism grounded in facts about our common human nature. Human beings inevitably develop, via a complex character formation involving a profoundly social process of reflective habituation, a second nature consisting of the virtues.(20) Our human nature is common, but our common human nature supports only a limited number of coherent and viable second natures.

Again for philosophers, bringing CT into discussions of virtue ethics and the connatural knowing of the virtuous, permits us to finally make progress on the vexed question of the unity of the virtues. From CT, we have suggestive empirical evidence for how and why it is possible to find virtues arranging themselves in characteristic clusters. Yet, while it is probably true that all of the virtues are found in some degree within any virtuous individual, virtuous individuals are themselves situated within a particular way of life and employ forms of practical rationality characteristic of that way of life. There will thus be systematic variations of emphasis as well as systematic content differences among virtues that go by the same name. Empirical studies can ground our understanding of the analogous use of virtue terms at both the intra-group the inter-group levels.

Interestingly, being situated within a particular way of life will tend to create characteristic areas of moral blindness. Ethicists can explore, in a more sensitive way than previously possible, which moral objects are likely to be overlooked and which are likely to be prominent to virtuous individuals speaking from different ways of life. Philosophers can take their cue from social scientists and social psychologists on how to investigate where these moral blind spots occur. Ethicists can then work together with their social science colleagues to solve the pressing normative problem of how to call these moral blind spots to general consciousness.

Finally, for philosophers, there is an empirical dimension brought to the study of ethics that I find most congenial. We need to overcome the dreadfully truncated visions of deontology and consequentialism. Let us instead ground our moral judgments in the richer soil of what is empirically good or bad, useful or non-useful, to beings possessed of a common human nature. I am indeed content to take a cue from what is to gain insight into what should be. For part of what is within any characteristic form of rationality is an embedded account of what should be. And here in the conjunction of CT, virtue ethics, and connatural knowledge, we have the foundations of a bridge across the is-ought divide.(21)

Notes:

8.20. Rationality, Ethical Incommensurability and Existential Communication

Sektionsgruppen | Section Groups | Groupes de sections

| Inhalt | Table of Contents | Contenu 17 Nr. |

Webmeister: Gerald Mach last change: 2011-11-29