Nr. 18 Juni 2011 TRANS: Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften

Section | Sektion: Signs and the City. In honor of Jeff Bernard

Cityscapes: A Trip across the US in Popular Song

Martina Elicker (English Department University of Graz, Austria) [BIO]

Email: martina.elicker@uni-graz.at

Konferenzdokumentation | Conference publication

Abstract:

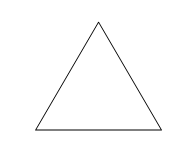

This paper proposes an illustration of how American popular music from the 1960’s through 1990’s makes use of and (re-)creates images of city life. US society has essentially been considered an urban society for the past one hundred years, which also explains and justifies the interest of American songwriters to deal with urban settings and life-styles in many of their songs. Depictions of urban ways of life in popular music range from the glorification of city life to the deploration of the loss of humanity and sensitivity in big cities. Implicitly drawing on semiotic models of music analysis (above all, Root’s triangle [1986: 17]), the paper attempts a trip across the US as presented in eight selected songs, focusing on the portraits of metropolises such as New York City and Los Angeles, but also of lesser known industrial towns, e.g. Allentown, PA. Idealizations of city life are juxtaposed with critical stances; musical means of representing the city are discussed in combination with an analysis of verbal descriptions. All representations automatically trigger further associations in the listeners, thus initializing what Peirce (quoted in Eco 1976: 69) refers to as “unlimited semiosis”.

Introduction

This paper aims to illustrate how American popular music from the 1960’s through 1990’s makes use of and creates/recreates images of the city. Popular music as a musical genre is considered an “urban” phenomenon, which for this reason alone lends itself to an analysis within the scope of urban semiotics. As Gillett (1970: i) points out,

Rock and Roll was perhaps the first form of popular culture to celebrate without reservation characteristics of city life that had been among the most criticized. In Rock and Roll, the strident, repetitive sounds of the city life were, in effect, reproduced as melody and rhythm.

Similarly, Chambers (1985: 210) states that

[i]f romance is the central medium of pop, and the body its privileged sounding board, it is the city that provides its fundamental stage. The city is the urban ‘body’, the place of the contemporary imagination; and through the technological reproduction of the imaginary, metropolitan textures […] enter every corner of our lives.

The fact that a great number of American popular songs deal with the city and its life-styles can in itself be considered a reflection of America as an essentially urban society in the twentieth and the twenty-first centuries. In the minds of many Americans, the city has to a large extent replaced the myth of the Western frontier as the place where freedom, fame, and fortune could readily be attained. Yet, despite this originally rather positively connoted view of city life, many ambivalent notions of city cultures have been encountered in popular music over the past few decades. Americans obviously can be simultaneously attracted and repelled by the city: hence, associations of narrowness, narrow-mindedness, and limitations with small-town life are often juxtaposed with the “big-city opportunity theme” (Cooper 1982: 108). On the other hand, these opportunities – usually connected to job and social upward mobility – are frequently depicted as repetitive, monotonous, boring, and dehumanizing. Urban life is consequently also described as crushing the spirit of talented, daring individuals because it lacks sensitivity, tends to produce loneliness and isolation, and creates fear of failure. Thus, in some songs, the sole preservation of the individual’s sanity is seen in his/her leaving the inner city to find personal gratification and escape the pressures of urban existence. This attitude displayed in pop songs coincides with the tendency of the American population to move out of the inner cities to suburbia.

The ambivalent stance of Americans toward urban settings and life-styles is clearly mirrored in popular music’s portraits of the city: some songs glorify city life (e.g. Petula Clark’s Downtown and Neil Diamond’s Beautiful Noise), whereas others highlight the negative aspects associated with urban centers: white collar vs. blue collar, ethnicity, racism, ghetto life, poverty, pollution, unemployment, disillusionment, and economic depression (e.g. Bruce Springsteen’s My Hometown and Billy Joel’s Allentown).

In the following section, a musical trip across the US will be undertaken, starting with an analysis of popular songs dealing with cities on the East Coast, moving on to the center of the country and ultimately the West Coast. The eight songs selected are discussed briefly, combining both the linguistic and musical performance as “types of semiotic praxis” (Sawyer 1996: 272) in their cultural context. The analysis draws on the semiotic triads proposed by Root (1986: 17), Tagg (1982: 40), and Nattiez (1990: 46), in which the discussion of the material song itself becomes a unit with the actual performance of the song and its reception by the audience:(1)

composition (Root) ~ channel (Tagg)

~ neutral level (Nattiez)

[lyrics – melody – arrangement]

performance (Root) ~ emitter (Tagg)

performance (Root) ~ emitter (Tagg)

~ poietic level (Nattiez)

[subject – speaker / persona – audience] response (Root) ~ receiver (Tagg)

~ esthesic level (Nattiez)

[occasion – judgment – taste]

The songs present different views of city life, spanning the more optimistic, flamboyant 1960’s (e.g. Scott McKenzie’s San Francisco), the street-wise 1970’s and 1980’s as described by the likes of Bruce Springsteen and Billy Joel, and the 1990’s (e.g. Marc Cohn’s Walking in Memphis). All songs(2) are representative of social developments and changes within American society, encompassing anything from the Hippie movement of the late 1960’s to race riots and social uproars through much of the late twentieth century.

City images are conjured up in various ways, ranging from musical representations such as the imitation of (New York) city noises including honking horns at the beginning of Neil Diamond’s Beautiful Noise or the use of gospel elements to depict a Southern urban feeling in Cohn’s Walking in Memphis to verbal descriptions of city life in the song lyrics. All the chosen songs construe and reinforce urban images and stereotypes among the listeners, who in turn envisage their own ideas, associations, memories, and clichés, which completes the cycle of “unlimited semiosis” (Peirce in Eco 1976: 69). As can be seen in the discussion of Randy Newman’s I Love L.A., associations with the city can also be intensified in the audience’s imagination by the imagery promoted in commercial videos released for particular songs.

Analysis of Musical Cityscapes: Eight Cases in Point

New York City has been the topic of many popular songs throughout history. Most of the time, the city has been glorified, which can also be experienced in the two songs analyzed here: Neil Diamond’s 1976 song Beautiful Noise and Petula Clark’s 1965 hit Downtown.

Beautiful Noise is probably the most interesting song in this study as to musical means and meta-musical language use: it is an uplifting, colorful ode to the sounds of the city and to the creative process urban ‘noises’ trigger in the songwriter. According to Diamond, the song was actually inspired by his daughter visiting with him at the Sherry-Netherland Hotel in Manhattan, and her looking out the window and remarking, What a beautiful noise (Hilburn 1992: CAL 62). The oxymoron of “beautiful” and “noise” is used throughout the song, connecting various notions of ‘noise’, e.g. the onomatopoetic “clickety-clack of a train on a track” and the “song of the cars on their furious flights”. The city noises, often associated with nuisance rather than beauty, are euphemized by Diamond in that they receive musical attributes such as “symphony”, “song”, “rhythm”, and “tune”. The city in all its facets (i.e. “a symphony played by a passing parade”) is equated with life (“the music of life”). Its diverse features are always inextricably linked to music: the noise from the street has got “a beautiful beat”, the train on the tracks has got “a rhythm to spare”, the kids in the park emit a “song” which “plays until dark”, the cars also create a song, which triggers a “beat”, a rhythmic movement reminiscent of a dance. These metaphors reinforce positive connotations of city life in the listener: “joy”, “strife”, and “romance” are gained from the hectic noises of the city.

This musical conception of urban life is emphasized from the very beginning of the song, which features recorded city and street noises, such as car horns, car engines, people talking and walking, and mixes them up front with synthesized street sounds. The introduction builds from pianissimo to mezzoforte and brings in a steady drum beat and the metal sound of Diamond’s Dobro guitar, which eventually replace the street noises and segue into the song’s actual melody and rhythm. The song’s tempo is moderately fast, which denotes the liveliness, vivaciousness, and passions of the city. The rhythm is steady yet vivid, reminiscent of the city’s ‘heartbeat’, its pulse. The exceptionally great number of syncopations and acciaccaturas (i.e. grace notes) adds considerably to the unpredictability and restlessness of the tune, indicative of the fickle ‘life in the fast lane’ of New York City. The key change from D major to C major in verse 3 (pivot chord modulation) supports the notion of flexibility and change in the metropolis.(3)

Downtown was written by Tony Hatch in 1964, inspired by his recent first trip to New York City (Wikipedia 3 [online]), and was subsequently recorded by Petula Clark, for whom it became a major hit both in her native England and in the US in 1965. Similarly to Beautiful Noise, Downtown is an upbeat, bouncy, rather fast tune with an optimistic message: the city makes people forget about their problems (“you can forget all your troubles, forget all your cares, so go downtown”, “when you’ve got worries, all the noise and the hurry seems to help, I know – downtown”). As in Beautiful Noise, musical ideas are depicted as a driving force behind the vibrant, happy city life: “the music of the traffic”, “the noise and the hurry”. Like the Diamond song, Downtown also contains a key change, in this case from E major to F major, initiated by the instrumental break after the second chorus. Downtown also foreshadows a concept of an urban setting further promoted in Frank Sinatra’s 1979 hit New York, New York (penned by Fred Ebb and John Kander), of a “city that never sleeps”: there are plenty of activities to embark on in the city, from movies to dancing to meeting people and falling in love; hence, life in the metropolis makes its residents carefree and happy. Thus, ultimately, both Downtown and Beautiful Noise evoke positive, optimistic feelings of city life in the listener. Through musical means as well as verbal, often metaphorical imagery in both song lyrics, the city is depicted as a place of opportunity, freedom, creativity, and happiness.

This optimistic, possibly idealistic view of urban culture and life-style is obviously refuted in two other songs about East Coast cities worth discussing in this context, Billy Joel’s Allentown and Bruce Springsteen’s My Hometown. Similarly to Lou Reed’s 1989 concept album New York, in which the singer-songwriter uses New York City as a metaphor for the entire American experience, criticizing materialism, corruption, and racism, Joel and Springsteen highlight economic depression, unemployment, social pressure, and the individual’s disillusionment at promises unfulfilled by US politics, the educational system, and the economy. Allentown has become an anthem of blue-collar America, representing both the aspirations and frustrations of America’s urban working class in the late twentieth century. The song was inspired by the demise of the East Coast manufacturing industry in the 1970’s and 1980’s, threatening the livelihood of the blue-collar neighborhoods of Allentown and Bethlehem, PA, in particular. The residents of these two industrial cities suffered from the decline and ultimate closure of Bethlehem’s Steel manufacturing industry, which had guaranteed relative prosperity to the communities for decades before it started to fade in the 1970’s. The happier past of the two communities (“our fathers […] spent their weekends on the Jersey Shore, met our mothers at the USO(4), asked them to dance, danced with them slow”) is contrasted with the bleak present and future: “killing time filling out forms, standing in line” obviously makes reference to the local population’s high unemployment rate, their lining up for unemployment benefits, while “we’re waiting here in Allentown for the Pennsylvania we never found, for the promises our teachers gave if we worked hard, if we behaved” refers to the people’s disillusionment in view of their future, their frustration at having studied hard at school, yet not succeeding in life despite the promises they were given. Hence, all their efforts have not paid off; on the contrary, the unfortunate locals lack support by the factories, the trade unions, and fellow residents not affected by the economic recession. Throughout the song, this matter-of-fact portrait of a deadpan, run-down community is accented by the steady, rough, hammering rhythm of percussion, acoustic guitar, and the piano, and by the rather monotonous melody in G major, which consists predominantly of descending lines. The introductory rhythm of the song and the repeated use of shhh-sounds are reminiscent of “the sound of a rolling mill converting steel ingots into I-beams or other shapes” (Wikipedia 1 [online]). Interestingly, although a major hit for Joel in 1983 world-wide, the song was met with mixed responses in Allentown itself. Some criticized the song as promoting a stereotypical, degrading view of a place the songwriter had never lived in himself, while others, including the audiences at his concerts in the area, were rather enthusiastic about the portrait of their gritty city (Wikipedia 1 [online]).

As does Joel in Allentown, Bruce Springsteen juxtaposes the more glorious past of the narrator’s unspecified Jersey hometown in My Hometown with its desolate present and future. Status symbols such as the “big old Buick”, symbol of American mobility and flexibility as well as the then-booming American car manufacturing industry, are linked with the prosperity and happiness of the old days, and with the residents’ pride in living in this city. This idyllic image is followed by a portrayal of the city as a dangerous, violent place filled with racial conflict, tension, and fights in the 1960’s, and despair and unemployment in the 1970’s and 80’s: “Main Street’s whitewashed windows and vacant stores”, “they’re closing down the textile mill”, and “foreman says these jobs are going, boys, and they ain’t coming back” are indicative of lost jobs and hopelessness, which ultimately leads to the narrator contemplating leaving his hometown, which is now also his son’s hometown (see verse 3). The song comes full circle content-wise when the narrator drives his son around his hometown, making him “take a good look around”, just as his father had done with him at the age of eight (see verse 1). Yet, this time it is not pride and joy but sadness and devastation which are on the narrator’s mind, having the song end on a bitter note with little hope left for his family. Hence, the city and its industry are considered symbols of bad faith on the part of the powers; the narrator is virtually forced to move, which in turn at least potentially points toward “salvation and perhaps transcendence” (Scheurer 1991: 230), with mobility in twentieth-century America being seen “as synonymous with opportunity” (ibid). The bitter-sweet feeling contained in the lyrics is also reflected in the music: on “This is your hometown”, the music quietly fades into the background until heard no longer. Similarly to Allentown, the monotonous melody, based on the chord progression of E – A – D in A major, built on variations of the three note motif and its expansion, and the steady beat emphasize the downbeat message contained in the lyrics. The frequent use of pedal points and off-beats denotes tension, suspense, and conflict. Also, the basic guitar-anchored arrangement, the moderately slow tempo, and Springsteen’s raspy, hoarse voice(5) aptly reflect the hardship of life described in the text. When the singer-songwriter softens his tone on the fade at the end of the song, however, the voice assumes an almost woeful quality, which echoes the melancholic tinge of the song and lingers on with the listener long after the song has faded.(6)

Moving further west, another metropolis, Chicago, is at the center of attention in Mac Davis’s In the Ghetto, which became a major hit for Elvis Presley in 1969. Unlike the songs discussed previously, In the Ghetto is not written from the perspective of a ‘lyric I’ but that of an omniscient narrator who describes the life of a young man from his birth to his untimely death in the streets of Chicago. The city is portrayed as a cold, wintry place, with little warmth and hope to fill a young boy’s existence in the slums of the inner city. He is born to fail, which is clearly implied in the song’s original title, The Vicious Circle: born into a poor, crime-shaken neighborhood, with his mother deploring his birth as she cannot make ends meet (verse 1); neglected throughout his childhood (“a hungry little boy with a runny nose”), growing up in the streets, acquiring skills related to violence and crime rather than formal education, venting his anger and frustration (verse 3), which eventually leads to his violent death by a bullet in the cold Chicago streets (verse 4). As yet another baby boy is born in the ghetto in verse 5, the song comes full circle, providing little room for hope of a better, brighter future for the ghetto residents. In verse 4, the song shifts focus from a particular young man to the fate of “a [i.e. any] young man”, who becomes symbolic of any youth growing up in any ghetto. In the Ghetto obviously refers to the same mid-sixties riots as does verse 2 of Springsteen’s My Hometown. The predictability and universality of the life of people raised in poor neighborhoods are underscored by musical means: the AAAAA verse pattern of the song contains basically the same melody and moderately fast folk rhythm throughout, with some variations of the I-IIIm-IV-V triad chord progression in the key of A major. The fairly dissonant melody-harmony relationship, the many line-end melismas, and Elvis Presley’s darkly passionate, grave vocal delivery build up tension on the musical plane and thus reinforce the storyline and portrayal of the city as a desolate, hopeless place with no chance of escape for the individual. Hence, life in the inner city is depicted as a dead-end scenario, which leaves people desperate and powerless in view of their own fate, and ultimately kills them. This stance of the predestined individual stands in stark contrast to what is generally perceived of as the ‘typically American’ attitude toward life: provided you work hard toward your goals, you will be able to achieve anything you want in life.

Marc Cohn’s 1991 US Top 40 hit Walking in Memphis depicts the city in Tennessee from the personal point of view of a ‘lyric I’; the city is seen as representing a dichotomy between the secular and the sacred: “gospel in the air”, “’Tell me, are you a Christian child?’ And I said, ‘Ma’am, I am tonight’”, and reference to Al Green sermons (“Reverend Green be glad to see you when you haven’t got a prayer”) clearly represent the musical and religious flavors present in the city and the ‘Bible Belt’ area of the US in general; they are married with secular, sexual images: “the land of the Delta Blues” references the more sensual type of music (compared to gospel music) very popular in the southern US, which is said to have its origin in Memphis, while “catfish on the table” may not only indicate the inexpensive type of fish available to everyone in the south and traditionally consumed on Fridays in its fried form but also the standard Blues metaphor for sexual intercourse. The song can also be interpreted as a homage to Elvis Presley, whose name is almost synonymous with Memphis (“the ghost of Elvis”, “Graceland”, “his tomb”, “Jungle Room”(7) and “blue suede shoes”(8)). Hence, Memphis is portrayed as a city of music and religious, spiritual awakening, with one being inextricably linked to the other. This is emphasized by the many additional references to local music legends, such as blues singer W.C. Handy and “Muriel”, a local artist who used to perform at the Hollywood Café, a small music joint in Memphis (Songfacts [online]). Obviously, local color is also recreated by the mention of Memphis landmarks immediately associated by any listener with the city, e.g. “Beale” referring to Beale Street, and the afore-mentioned “Graceland”, both of which are clearly connected to Presley, the former being known as the home of the Blues and the birthplace of Rock’n’Roll, the latter now being a museum devoted to the music legend himself and considered a ‘shrine’ worthy of at least one pilgrimage to by many of the millions of Elvis fans around the globe. The piano-dominated song in C major with its crisp rhythm and soaring melody lines, underscored by an unusually large number of pedal points, makes clear reference to gospel music, and indirectly hints at blues elements as well. At the very beginning of the song, the sounds used indicate falling rain, which evidently foreshadows the lyric, “Touched down in the land of the Delta Blues in the middle of the pouring rain”. The song was reportedly inspired by Cohn’s visit to Memphis in 1986, where he witnessed a sermon by Al Green (Songfacts [online]), which must have impressed him so deeply as to come up with a gospel and Elvis Presley-tinged homage to southern, urban US life.

Randy Newman’s I Love L.A. juxtaposes life in Los Angeles with life in New York and Chicago, disqualifying New York as “cold” and “damp”, with its residents displaying bad taste in fashion (“all the people dressed like monkeys”), and Chicago as “too rugged”, to be left “to the Eskimos”. The official video released for the song features scenes from New York City and Chicago in black and white, then cutting to images of L.A. in bright colors, in order to contrast the city on the West Coast with the other two metropolises. Newman, himself an L.A. native, emphasizes his affection for his hometown, while at the same time keeping a critical eye on developments within society. He describes Los Angeles as warm (“Santa Ana wind blowin’ hot from the north”, “the sun is shining all the time”), making people “very happy”, cruising through town with their car tops down (“Roll down the window, put down the top”), listening to the bouncy, happy sound of the Beach Boys, ‘the incarnation’ of California beach culture (“Crank up the Beach Boys, baby, don’t let the music stop”), enjoying the beauty of the landscape (“Look at that mountain, look at that tree”). Appropriately, Newman is seen driving an open convertible through town with a beautiful redhead by his side in the video, drawing on a plethora of superficial stereotypes associated with L.A., from fancy cars to sandy beaches and beautiful women sporting tiny bikinis. The fact that the song also mentions the existence of homeless people in the streets (“look at that bum over there, man, he’s down on his knees”) and the video also features an L.A. “bum”, obviously making his home at the beach, perfectly illustrates Newman’s ambivalent, ironic attitude toward the city and the American Dream in general: on the one hand, there are beautiful women, joy, lightheartedness and – or maybe due to – the good weather; on the other hand, there are homeless persons roaming the streets, trying to survive. Hence, the chorus I love L.A., rendered rather dryly in the singer-songwriter’s raunchy, biting voice,(9) together with the many positive images throughout the song border on sarcasm. Indeed, the name Randy Newman alone automatically connotes irony and sarcasm.(10) Thus, by pointing out the dichotomy between superficial happiness and serious issues and problems in society, and applying irony, the song assumes a more profound, reflective quality. This disparity is also picked up on geographically in the coda of the song, in which Newman lists Los Angeles street names, alluding to some of the wealthiest and some of the poorest areas of the city: “Century Boulevard, Victory Boulevard, Santa Monica Boulevard, Sixth Street”.(11) The insertion of We love it by the backup singers after each mention of a street name reinforces the tongue-in-cheek tone prevailing throughout the song. Musically, I Love L.A. is built on a heavy beat dominated by percussion and electric guitar, with a very monotonous yet intense melody, written in A major with a modulation to C major in verse 5, after the first chorus. Obviously, the irony dominating the song is underlined by the musical delivery as well, communicated both on the interpretative / performative level and by the music per se, displaying a rather disharmonious melody-accompaniment relationship. Despite its critical stance, I love L.A. has been “appropriated by happy Angelenos as a new city song […]” (Marcus 1975/1997: 250) and is still played at most sports events in Los Angeles when the home-team, such as the L.A. Lakers, the L.A. Dodgers, and the L.A. Galaxy, has scored or won (Wikipedia 2 [online]).

The final song analyzed in this study, Scott McKenzie’s hit song San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair) has become synonymous with the Hippie movement and experience since its release in 1967. It was originally written by John Phillips of The Mamas & The Papas to promote the Monterey Pop Festival and instantly became a hit world-wide for McKenzie. The song was particularly popular in Central and Eastern Europe, where it was adopted by young people as an anthem for freedom, and it was widely played during the Prague Spring uprising in Czechoslovakia. It is also credited with bringing thousands of young people to San Francisco during the late 1960’s (Wikipedia 4 [online]). The song’s lyric and music both draw on the psychedelic flower-power experience: while the music is predominantly acoustic guitar, tambourine, and percussion-based, the text is built around the ‘make love, not war’ slogan of the Hippie movement. Notions such as love and social change are contained in “love-in”, “gentle people”, “people in motion”, “a whole generation, with a new explanation”, and “all across the nation, such a strange vibration”. San Francisco becomes symbolic of flower power (“be sure to wear some flowers in your hair”) and young people’s urge to initiate changes in the social make-up and US pro-warfare attitudes. The city and its ‘vibes’ (“vibration”, “motion”) stand for this movement toward a more peaceful worldview, new ideas and ideologies, in which, ultimately, the entire US nation (“a whole generation”, “all across the nation”) – and, ideally, the whole world – partakes.

Conclusion

As we have seen in the analyses above, ambivalence in the portraits of urban settings in US popular music prevails throughout the twentieth century. This dichotomy between idealized forms of city life and its downsides both reflects and emphasizes people’s perceptions of reality and their conceptions of what constitutes urban life-styles and cultures. Indexical usage of musical representations of city sounds (e.g. car horns) may (re-)create notions of the city as effectively as verbal references to urban phenomena (e.g. “noise”, “traffic”) and specifics of particular times and places in twentieth-century America (e.g. Hippie culture in San Francisco). Many of the linguistic allusions actually have an underlying musical concept of city life, as can be seen in both Beautiful Noise and Downtown, but also in Allentown, with its imitation of steel mill sounds. All songs discussed in this study are strongly influenced by the songwriters’ ideas of urban life, their social and cultural backgrounds, and by the times they were written and performed. San Francisco, removed from its temporal and societal context, would be void of meaning – at least in its obviously intended form. Similarly, songs such as Allentown and My Hometown assume more profound meaning only when considered in the context of when they were actually written. Logically, residents of Allentown, for instance, will have reacted differently, possibly more emotionally, to the song being performed live in concert by Joel in their socially deprived neighborhood than an audience in, say, New York City, which in turn will have impacted Joel’s performance of the song – hence the never-ending process of semiosis intrinsic to popular music performance. Thus, whether urban settings are viewed as a threat to individualism, creativity, and social wellbeing or as a driving force fueling creative processes and generating satisfaction and happiness in the individual, largely depends on the songwriter’s / performer’s as well as the listener’s respective experiences of city life and conceptions of urbanity, which will determine identification with either the celebration of urban culture or its open or implied criticism.

References

Printed sources:

- Barthes, Roland (1977). Image – Music – Text (translated by Stephen Heath). London: Fontana Press.

- Chambers, Ian (1985). Urban Rhythms. Pop Music and Popular Culture. London: Macmillan.

- Cook, Lez (1983). “Popular Culture and Rock Music”. Screen: 24 (3): 44-49.

- Cooper, B. Lee (1982). Images of American Society in Popular Music. A Guide to Reflective Teaching. Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers.

- Eco, Umberto (1976). A Theory of Semiotics. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP.

- Elicker, Martina (1997). Semiotics of Popular Music. The Theme of Loneliness in Mainstream Pop and Rock Songs. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.

- Gillet, Charlie (1970). The Sound of the City: The Rise of Rock and Roll. New York: Outerbridge and Dienstfrey.

- Hilburn, Robert (1992). “Songs Sung Blue… Diamond Reminisces”. Los Angeles Times. March 8, 1992: CAL 5, 62.

- Longhurst, Brian (1995). Popular Music and Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Marcus, Greil (1975/1997). Mystery Train. Images of America in Rock’n’Roll Music. Fourth revised edition. New York et al: Plume.

- Middleton, Richard (1990). Studying Popular Music. Milton Keynes, Philadelphia: Open UP.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Musical Discourse. Toward a Semiology of Music (translated by Carolyn Abbate). Princeton: Princeton UP.

- Nöth, Winfried (1990/1996). Handbook of Semiotics. Third edition. Bloomington, IN et al: Indiana UP.

- Root, Robert Jr. (1986). “A Listener’s Guide to the Rhetoric of Popular Music.” Journal of Popular Culture 20 (1): 15-26.

- Sawyer, R. Keith (1996). “The Semiotics of Improvisation : The Pragmatics of Musical and Verbal Performance”. Semiotica 108 (3-4): 269-306.

- Scheurer, Timothy E. (1991). Born in the U.S.A. The Myth of America in Popular Music from Colonial Times to the Present. Jackson and London: UP of Mississippi.

- Tagg, Philip (1982). “Analyzing Popular Music: Theory, Method, and Practice.” Popular Music 2: 37-68.

Webliography:

- “Allentown (song)”. Wikipedia.(1). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allentown_(song) [Sept. 20, 2010].

- “I Love L.A.”. Wikipedia. (2). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Love_L.A, [Sept. 28, 2010].

- “Petula Clark”. Wikipedia. (3). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petula_Clark [Sept. 13, 2010]. “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)”. Wikipedia. (4). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Francisco_(Be_Sure_to_Wear_Flowers_in_Your_Hair) [Sept. 29, 2010].

- “Songfacts: “Walking in Memphis by Marc Cohn”. http://www.songfacts.com/detail.php?id=67 [Sept. 27, 2010].

Discography:

- Clark, Petula (1964). “Downtown”. Downtown. Pye Records.

- Cohn, Marc (1991). “Walking in Memphis”. Marc Cohn. Atlantic Records.

- Diamond, Neil (1976). “Beautiful Noise”. Beautiful Noise. Columbia Records. Joel, Billy (1982). “Allentown”. The Nylon Curtain. Columbia Records.

- McKenzie, Scott (1967). “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in your Hair)”. Voice of Scott McKenzie. Repertoire.

- Newman, Randy (1983). “I Love L.A.”. Trouble in Paradise. Warner Bros. Records.

- Presley, Elvis (1969). “In the Ghetto”. From Elvis in Memphis. RCA Records.

- Sinatra, Frank (1979/1980). “New York, New York”. Trilogy: Past Present Future. Reprise.

- Springsteen, Bruce (1984). “My Hometown”. Born in the U.S.A. Columbia Records.

Music videos

- Clark, Petula (1964/1965). “Downtown”. Downtown. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FKCnHWas3HQ (live).

- Cohn, Marc (1991). “Walking in Memphis”. Marc Cohn. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4oAmQ00N14k (original, commercial video).

- Diamond, Neil (1976). “Beautiful Noise”. Beautiful Noise. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GE0R8Kpd8f4 (original); http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TEtj6ME-e2U (live).

- Joel, Billy (1982). “Allentown”. The Nylon Curtain. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BHnJp0oyOxs (original, commercial video).

- McKenzie, Scott (1967). “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)”. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bch1_Ep5M1s (original).

- Newman, Randy (1983). “I Love L.A.” Trouble in Paradise. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=le5aIqn_MfE (original, commercial video).

- Presley, Elvis (1969). “In the Ghetto” (single). http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2En0ZyjQgU4 (original); http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Ox1Tore9nw (live).

- Springsteen, Bruce (1984 1985). “My Hometown”. Born in the U.S.A. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=77gKSp8WoRg (live).

Appendix

Neil Diamond: Beautiful Noise

What a beautiful noise

Comin’ up from the street

Got a beautiful sound

It’s got a beautiful beat

It’s a beautiful noise

Goin’ on everywhere

Like the clickety-clack

Of a train on a track

It’s got a rhythm to spare

It’s a beautiful noise

And it’s a sound that I love

And it fits me as well

As a hand in a glove

Yes it does, yes it does

What a beautiful noise

Comin’ up from the park

It’s the song of the kids

And it plays until dark

It’s the song of the cars

On their furious flights

But there’s even romance

In the way that they dance

To the beat of the lights

It’s a beautiful noise

And it’s a sound that I love

And it makes me feel good

Like a hand in a glove

Yes it does, yes it does

What a beautiful noise

It’s a beautiful noise

Made of joy and of strife

Like a symphony played

By the passing parade

It’s the music of life

What a beautiful noise

Comin’ into my room

And it’s beggin’ for me

Just to give it a tune

(Diamond 1976)

Petula Clark (Tony Hatch): Downtown

When you’re alone and life is making you lonely

You can always go – downtown

When you’ve got worries, all the noise and the hurry

Seems to help, I know – downtown

Just listen to the music of the traffic in the city

Linger on the sidewalk where the neon signs are pretty

How can you lose?

The lights are much brighter there

You can forget all your troubles, forget all your cares

So go downtown, things’ll be great when you’re

Downtown – no finer place, for sure

Downtown – everything’s waiting for you

Don’t hang around and let your problems surround you

There are movie shows – downtown

Maybe you know some little places to go to

Where they never close – downtown

Just listen to the rhythm of a gentle bossa nova

You’ll be dancing with him too before the night is over

Happy again

The lights are much brighter there

You can forget all your troubles, forget all your cares

So go downtown, where all the lights are bright

Downtown – waiting for you tonight

Downtown – you’re gonna be all right now

[Instrumental break]

And you may find somebody kind to help and understand you

Someone who is just like you and needs a gentle hand too

Guide them along

So maybe I’ll see you there

We can forget all our troubles, forget all our cares

So go downtown, things’ll be great when you’re

Downtown – don’t wait a minute for

Downtown – everything’s waiting for you

Downtown, downtown, downtown, downtown …

(Hatch/Clark 1964/1965)

Billy Joel: Allentown

Well we’re living here in Allentown

And they’re closing all the factories down

Out in Bethlehem they’re killing time

Filling out forms

Standing in line.

Well our fathers fought the Second World War

Spent their weekends on the Jersey Shore

Met our mothers at the USO

Asked them to dance

Danced with them slow

And we’re living here in Allentown.

But the restlessness was handed down

And it’s getting very hard to stay…

Well we’re waiting here in Allentown

For the Pennsylvania we never found

For the promises our teachers gave

If we worked hard

If we behaved.

So the graduations hang on the wall

But they never really helped us at all

No they never taught us what was real

Iron or coke,

Chromium steel.

And we’re waiting here in Allentown.

But they’ve taken all the coal from the ground

And the union people crawled away….

Every child had a pretty good shot

To get at least as far as their old man got.

If something happened on the way to that place

They threw an American flag in our face, oh oh oh.

Well I’m living here in Allentown

And it’s hard to keep a good man down.

But I won’t be getting up today…

And it’s getting very hard to stay.

And we’re living here in Allentown.

(Joel 1982)

Bruce Springsteen: My Hometown

I was eight years old and running with a dime in my hand

Into the bus stop to pick up a paper for my old man

I’d sit on his lap in that big old Buick and steer as we drove through town

He’d tousle my hair and say son take a good look around

This is your hometown, this is your hometown

This is your hometown, this is your hometown

In ‘65 tension was running high at my high school

There was a lot of fights between the black and white

There was nothing you could do

Two cars at a light on a Saturday night in the back seat there was a gun

Words were passed in a shotgun blast

Troubled times had come to my hometown

My hometown, my hometown, my hometown

Now Main Street’s whitewashed windows and vacant stores

Seems like there ain’t nobody wants to come down here no more

They’re closing down the textile mill across the railroad tracks

Foreman says these jobs are going, boys, and they ain’t coming back to

Your hometown, your hometown, your hometown, your hometown

Last night me and Kate we laid in bed talking about getting out

Packing up our bags maybe heading south

I’m thirty-five we got a boy of our own now

Last night I sat him up behind the wheel and said son take a good

Look around

This is your hometown

(Springsteen 1984/1985)

Elvis Presley (Mac Davis): In the Ghetto

As the snow flies

On a cold and gray Chicago mornin’

A poor little baby child is born

In the ghetto

And his mama cries

‘cause if there’s one thing that she don’t need

it’s another hungry mouth to feed

In the ghetto

People, don’t you understand

the child needs a helping hand

or he’ll grow to be an angry young man some day

Take a look at you and me,

are we too blind to see,

or do we simply turn our heads

and look the other way

Well the world turns

and a hungry little boy with a runny nose

plays in the street as the cold wind blows

In the ghetto

And his hunger burns

so he starts to roam the streets at night

and he learns how to steal

and he learns how to fight

In the ghetto

Then one night in desperation

a young man breaks away

He buys a gun, steals a car,

tries to run, but he don’t get far

And his mama cries

As a crowd gathers ‘round an angry young man

face down on the street with a gun in his hand

In the ghetto

As her young man dies,

on a cold and gray Chicago mornin’,

another little baby child is born

In the ghetto

(Davis/Presley 1969)

Marc Cohn: Walking in Memphis

Put on my blue suede shoes

And I boarded the plane

Touched down in the land of the Delta Blues

In the middle of the pouring rain

W.C. Handy – won’t you look down over me

Yeah I got a first class ticket

But I’m as blue as a boy can be

Then I’m walking in Memphis

Walking with my feet ten feet off of Beale

Walking in Memphis

But do I really feel the way I feel

Saw the ghost of Elvis

On Union Avenue

Followed him up to the gates of Graceland

Then I watched him walk right through

Now security they did not see him

They just hovered ‘round his tomb

But there’s a pretty little thing

Waiting for the King

Down in the Jungle Room

(Chorus)

They’ve got catfish on the table

They’ve got gospel in the air

And Reverend Green be glad to see you

When you haven’t got a prayer

But boy you’ve got a prayer in Memphis

Now Muriel plays piano

Every Friday at the Hollywood

And they brought me down to see her

And they asked me if I would

Do a little number

And I sang with all my might

And she said –

“Tell me, are you a Christian child?”

And I said, “Ma’am, I am tonight”

(Chorus)

Put on my blue suede shoes

And I boarded the plane

Touched down in the land of the Delta Blues

In the middle of the pouring rain

Touched down in the land of the Delta Blues

In the middle of the pouring rain

(Cohn 1991)

Randy Newman: I Love L.A.

Hate New York City

It’s cold and it’s damp

And all the people dressed like monkeys

Let’s leave Chicago to the Eskimos

That town’s a little too rugged

For you and me, you bad girl

Rollin’ down the Imperial Highway

With a big nasty redhead at my side

Santa Ana wind blowin’ hot from the north

And we was born to ride

Roll down the window, put down the top

Crank up the Beach Boys, baby

Don’t let the music stop

We’re gonna ride it till we just can’t ride it no more

From the South Bay to the Valley

From the West Side to the East Side

Everybody’s very happy

‘Cause the sun is shining all the time

Looks like another perfect day

I love L.A. (We love it)

I love L.A. (We love it)

Look at that mountain

Look at that tree

Look at that bum over there, man

He’s down on his knees

Look at these women

There ain’t nothin’ like ‘em nowhere

Century Boulevard (We love it)

Victory Boulevard (We love it)

Santa Monica Boulevard (We love it)

Sixth Street (We love it, we love it)

I love L.A.

I love L.A.

(We love it)

(Newman 1983)

Scott McKenzie (John Phillips): San Francisco

If you’re going to San Francisco,

Be sure to wear some flowers in your hair.

If you’re going to San Francisco,

You’re gonna meet some gentle people there.

All those who come to San Francisco,

Summertime will be a love-in there.

In the streets of San Francisco,

Gentle people with flowers in their hair.

All across the nation, such a strange vibration,

People in motion,

There’s a whole generation, with a new explanation,

People in motion, people in motion.

All those who come to San Francisco,

Be sure to wear some flowers in your hair.

If you come to San Francisco,

Summertime will be a love-in there.

(Phillips/McKenzie 1967)

Notes:

1 The mutual performer–audience influence is, of course, much stronger and more evident in live performances of popular music, an aspect largely neglected here as it would go beyond the scope of this paper. 2 The song lyrics of the eight songs discussed can be found in the appendix. 3 For a more detailed discussion of “Beautiful Noise” see Elicker (1997: 163-164). 4 USO refers to the United Service Organizations, Inc., a private, non-profit organization that provides recreational services to members of the U.S. military. 5 The phenomenon of immediately associating a particular voice quality with a particular singer is referred to by Barthes (1977: 179-189) as the “grain of the voice”. 6 For a more detailed study of “My Hometown” see Elicker (1997: 86-90). 7 The “Jungle Room” was one of the rooms in Presley’s mansion “Graceland”. 8 A reference to the Presley hit song “Blue Suede Shoes”. 9 See footnote 5. 10 Middleton (1990: 232) refers to this phenomenon within secondary signification (i.e. connotation) as “rhetorical connotations”, i.e. “associations arising from correspondences with rhetorical forms […] and styles”. 11 The reference to the “Imperial Highway” in verse 2 already marks the traversing from poor to rich neighborhoods.

Inhalt | Table of Contents Nr. 18

For quotation purposes:

Martina Elicker: Cityscapes: A Trip across the US in Popular Song –

In: TRANS. Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften. No. 18/2011.

WWW: http://www.inst.at/trans/18Nr/II-1/elicker18.htm

Webmeister: Gerald Mach last change: 2011-06-17