Fig. 1

| Trans | Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften | 16. Nr. | Juni 2006 | |

|

5.6. Border Zones: Travel, Fantasy and Representation Herausgeberin | Editor | Éditeur: Ludmilla Kostova (University of Veliko Turnovo, Bulgaria) |

||||

Travel Legends and E-space

Gergana Apostolova (South Western University, Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria)

[BIO]

Legends represent a separate field of semi-fantastic narrative where real life report merges with the space of artistically woven desire, building a new type of awareness and destroying the limitations of the subconscious.

Unlike fiction and very much like folklore, legends are bound to real places. They do not remain there, though, for they are free to cross borders. In the first place, they cross the borders of the physical world to enter upon the realms of fantasy-woven narrative. In the second place, they cross the limitations of a specific culture to enter upon fundamental human values. This is characteristic of the greater part of legends.

There are also legends, which cross the borders of real geography and history and take us to places and times and to events that may have happened "really", but are caught in a tangle of fantastic logic. Such legends melt cultural barriers by assuming that their dramatis personae are just people who mind their own business within a changing environment. That latter group of legends is the object of our study and we shall call them "travel legends" for they transgress cultural spaces.

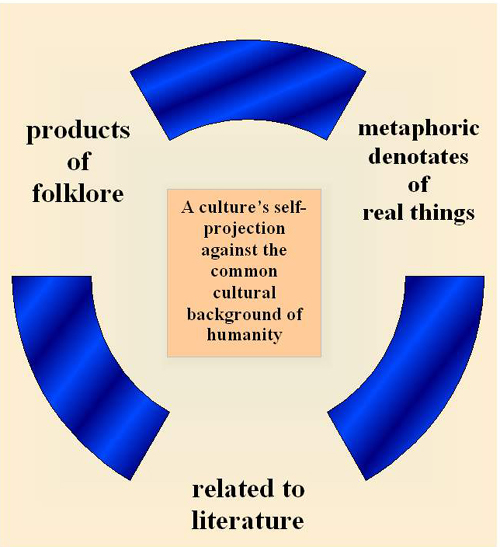

Travel legends have four basic features:

they are products of folklore and as such represent cultures as the latter have seen themselves against a broader background;

they are metaphoric denotates of real things;

they are related to literature in the way folklore is related to it, serving as sources or crossroads of infinite text;

they are proto-forms that use features of travel writing. (Fig. 1)

In displaying all these features travel legends open routes and cross borders, taking us back to the common cultural ground of humanity of earlier time, preserved in rigid artistic forms, binding emotion and image with value.

Fig. 1

In the age of techno-oral culture (Lévy 1997:197) the art of story telling has found new spaces to conquer by reviving ancient fantasies to high-tech-supported adaptations and extensions reaching far into the motivation of the individual consciousness raised within the clashing values of ethnic identity and global humanity.

If Arabian Nights have left their touch on all our folklore and tales of the exotic, if Border Ballads have entered the world of gamebooks and late 20 th-century fantasies, if Stephen King has employed the boat running along the "gutter swollen with rain" which has reached It through the tale of the Brave Tin Soldier and Alice’s sea of tears, if the Discworld is possible, then borders have merged swept by the spreading wings of fantasy, and eventually the cultural membrane of the 21 st century has proven benevolent to revived archetypes.

Cultural borders melt in the realm of fantasy where text is infinite space within supple limits.

Still there are texts, built on archetypes, which have not entered the space of modern fantasy.

While the folktale has populated dark forests with wood nymphs, werewolves, vampires, dragons, lamias, witches, shepherds, bears and foxes, giving jobs to good and bad girls and brave young men, - thus closing off this dream world from the common practices of real people, legends, which fix on activities and attitudes started by everyday routine and having tangible effects, have not yet passed successfully the borders of modern fantasy, and have but very limited access to the space of the world wide web.

Starting with travel legends, we shall seek to establish opportunities and features that enable translegendary existence in the e-space of present burgeoning cyberculture.

Legends are liminal to folklore and literature for they link "real" places, characters and events with the realms of desire and fantasy.

Space is the most important feature in legends: they are for the most part bound to a place and purport to provide explanation about its settlement, desertion, importance or name. Being bound to functions legends have cultural, pragmatic and/or onomastic value which provides grounds for motivation, local pride, artistic creation and development of the business of tourism.

Travel legends, unlike most other legends, are bound to an agent (a person or an object) rather than to a place. They span bridges over spaces where geography and history form individual patterns. As with travel writing, all geographies are imaginative geographies—fabrications in the literal sense of "something made" -and our access to the world is always made through particular technologies of representation. (Duncan-Gregory 1999:5)

The specific technology of representation in travel legends involves two sets of features: 1) realistic description of places, routes, directions and distances with a focus on single details with specific meaning for the particular legend; 2) an unfixed temporal dimension where the places are seen as cutting through historical epochs in a single narrative. In travel legends dramatis personae travel from place to place while places move through time, and cultures of different types happen to visit the legendary space turning it into a common ground for humanity.

There is an aspect, which can serve as the door for letting legends into the space of the Internet, especially travel legends, which resemble travel writing in being concerned with the spatiality of representation. In them the latter is resolved as "an act of translation that constantly works to produce a tense ‘space in-between’. Defined literally, "translation" means to be transported from one place to another, so that it is caught up in a complex dialectic between the recognition and recuperation of difference" (Miller 1996). Memory, especially collective or social memory, is also a form of translation "marked by a boundary crossing and by a realignment of what has become different" (Iser 1996, 297; see also Motzkin 1996, 265-81). But, as Maurice Halbwachs’s study of the cultural construction of the Holy Land and its pilgrimage routes reminds us, social memory is often sedimented through circuits in space. In representing other cultures and other natures, then, travel writers "translate" one place into another, and in doing so constantly rub against the hubris that their own language-game contains the concepts necessary to represent another language-game (Dingwaney 1995, 5; Asad and Dixon 1973; 1985; Duncan-Gregory 1999:4).

This specific translation of cultures is based on the transformation of symbols, rendering them less specific and thus bringing them nearer to a common cross-cultural understanding or in the terms of Duncan-Gregory - occupying a space-in-between cultures (Duncan-Gregory 1999:5).

Travel legends, like travel writing, report of colonizing power and imperial gestures (Duncan-Gregory 1999:5), using both the domesticating method and foreignizing method of translation which either bring the reader or the hearer of the legend back home or send him/her abroad (Venuti 1993:210). The fantastic setting of the legendary narrative, however, makes these processes happen simultaneously providing space for all cultural elements, where the boundaries are not between cultures but are of a more general nature asserting fundamental choice and existential value. Travel legends unite movement and stability, searching for identity through ‘otherness’ and building community through the displacement of their characters.

Legendary space is likewise connected with gender performance: generally, masculinity is interpreted as involving movement and displacement, while femininity is linked to stability and bonding, which create environment and power for masculine action. Yet there is no limit to human nature and roles sometimes change in legendary narrative whether desired and fantastic or realistically reported.

The space of legendary action forms an infinity, which can easily transform into e-space where this "translation" would not unify but preserve their specifics.

As I have remarked elsewhere (Apostolova 2006), E-culture is the sphere containing all controlled (primary) and automated (secondary) processes, human activities, relations and products realized in virtual space. At this stage of its development it is characterized as a specific extension to traditional human culture: it is both its product and its adaptation.

The characteristics of virtual culture are as follows: it is communicative; it has a technical carrier; it uses energy from an outside source; it exists only for those who have access to it. These features determine the outside boundaries of virtual culture fixing its practices, dramatis personae, rituals and values within matrices. The vast continuum of traditional culture is contained in those matrices. Virtual adaptations of culture are interpretations where the present plays the role of an interface letting only the current image of culture - its existence for the "now" - its dimensions reduced to the point of the moment - its significance for the virtual individual regardless of the innumerable interpretations or significances of the same events for generations of human individuals. The change of functioning of culture is consequent upon the change of communicative reality where the source, the encoder, the channel, the noises, the decoder and the user employ new means to produce a message different in form, intention and effect while using the same material traditional culture has supplied.

Virtual culture and its ethical system in particular are based on the cybernetic mechanisms of extending human consciousness. The traditional essentialist view relates culture to a physical entity: a place, a country, a language (Holliday- Hyde-Kullman 2004:4-5) which have to be translated in the process of intercultural communication. A non-essentialist description of culture sees it as a social force, based on values and characterized by complexity and a discourse as much as by a language and unfixed within boundaries where "people are influenced by or make use of a multiplicity of cultural forms" (Holliday- Hyde-Kullman 2004:4-5). Cyberculture can be seen simultaneously from both points of view: it has a space and means of communication, while using a multiplicity of cultural forms.

Cyberculture has created a vast space for fantasy where legends as core texts have a nearly invisible presence.

Our basic problem of concern here is how is it possible to make space for legends, especially those of cross-cultural value, within the borders of e-space, passing them as cultural objects through the interface of e-culture.

The features of travel legends that enable their transformation into e-space are as follows:

| Translatable Features of Travel Legends | Corresponding Features of E-culture |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Further we shall test the archetypal framework of a couple of legends as providing sets of features for building the ontology of translegendary texts.

Legends are definitely culture-laden. Malinowski (1926:58) cautioned that myth, taken as a whole, cannot be sober dispassionate history, since it is always made ad hoc to fulfil a certain sociological function, to glorify a certain group, or to justify an anomalous status. Legends, for their part, "in any society combine a variety of functions and types of information" (Dixon 1996).

If we assume that " to the native mind immediate history, semi-historic legend, and unmixed myth flow into one another, form a continuous sequence, and fulfil the same sociological function " (Dixon 1996), then a legend is self-centered. It draws the cultural focus over its object of representation. That makes legends diverse in cultural content yet of the same structure. One and the same object of narration can be opposed as in the case with the representation of the Balkans in nineteenth-century British writing where " the distinction between dominant centre and dominated periphery had played a major role in the master narratives of Eurocentrism in which (North) Western Europe had inscribed itself as the centre of civilization and progress, reserving for itself only the right to 'represent' the 'old' continent" (Kostova 1997:11) The beginning of the eighteenth century saw an increasingly influential tendency of viewing Europe and the rest of the world in terms of clear-cut distinctions between East and West, between civilization and primitivism. It further saw the division of Europe into "centres" and "peripheries". Parts of Eastern and Southern Europe assumed the latter status. The process involved the production of national mythology stressing British exceptionality and making amends for ethnocentric attitudes by designating freedom, prosperity, and advancement as distinctively British characteristics (see: L. Kostova 1997:28).

In the legends cited here the opposite process is in evidence: the focus is changed and the immediate setting is represented as "the centre" even when viewed against an empire or a more influential culture.

The texts chosen here exemplify the features of travel legends as discussed above. Thematically they represent three narrative archetypes built around the axis of permanence and transformation: origin and fate, transcendence and love, bonding and sacrifice. The texts are original and can be viewed as sources and crossroads of intertexts, which are worth passing through the membrane of cyberculture. Their value basis is simple which makes it possible that they form a set of ontology features.

The texts preserve their original form as I have read or heard them from native informants in Plovdiv (central Bulgaria) and Kyustendil (near the western border of Bulgaria).

Table 1: Legend Texts

(1) The Seven Hills of Plovdiv |

(2) The Legend of the Rose |

(3) The Mason |

In times immemorial in a Thracian village near the Maritza there arrived messengers of the Persian shah sent to search for an heir to the throne since the shah had no son. They noticed a young boy of unusual stature and behaviour, liked him and took him with them. The boy grew up and became the ruler of Persia. Three times his mother sent his brother to him with a warm plead: for help against foreign invaders, for wheat to save the tribe from famine, and for him to come to her death bedside. Three times the king of Persia refused. The sick woman cursed him: "Your heart has turned into stone. If it happens that your step touches our land again let you turn into stone!" When he died a caravan of seven camels carrying his coffin and 6 loads of precious stones and gold arrived at the village near the Maritza. The moment the coffin of the dead king touched the ground everything turned into stones. Later on the winds blew dust and seeds all over them, the rains watered them and they turned into seven hills around which the old Thracian village spread into a town, called Julia by the Romans, Puldin by the Slavs, Philipopolis by the Macedonians and the Byzantines, Philipovgrad by the Bulgarians, Filibe by the Turks to pass through crossing and re-crossing Balkan histories and emerge nowadays as the multi-ethnic town of Plovdiv. |

A Bulgarian artisan travelled to the kingdom of Abass shah and built for him a palace of unseen beauty. While the construction of the palace was in process Leila, the princess, fell in love with the master. The shah expelled him but before he left Leila met him in the garden where white roses grew, picked a bush and gave it to him as a token of their love. Her hands bled injured by the thorny bush and a few drops fell on the blossoms. When the mason took the bush to his native valley huddled in the Balkans it thrived and spread covering the green glades of May with pink flowers. People made perfumes out of their tears and the place is now known as The Valley of the Rose. |

There was a famous mason who could build houses and bridges, palaces and fountains of unusual beauty. However, in order to make them sound he had to build into them the people who came to him first thing in the morning: his nearest and dearest - his wife or sister, a young bride, his first son. This legend has been adopted by the Bulgarian gypsies who tell it in a number of variations.

(3a) The Source of the White-Footed Maiden Gergana was a beautiful lass who used to go to a source near her native village. A Turkish vizier passed once there with his men, fell in love with her and asked her to go with him to Istanbul. She refused. Charmed by her, he ordered a fountain to be built in her honour. The masons built her shadow in the stone. She died shortly after that. Her shadow still appears on moonlit nights round the place, and there can also be heard the sad tune of her young man’s flute.

(3b) The Bridge of Kadina Kadina was a young mother with a new-born baby. She was immured into a bridge by the builder - her brother, and there was a hole left so that she could feed her baby through it when they carried it to her in the day. Her milk made the bridge sound and it is still there over the Struma connecting the two parts of the village of Nevestino. |

The texts have a clear structure which allows it to isolate the core symbols containing the travel legend and making its translation into the e-space unicultural environment possible. The symbols in question denote space, movement and bonding.

The space of the travel legend usually has two or three layers since it refers to geographical position, temporal markers, social markers and emotional aspects. It is split into the opposition of here and there with its variation of centre - periphery and their concrete expressions: home - abroad; home - the wide world; home - foreign; real - imaginary/ desired/ supernatural. Movement as in travel writing makes a loop of there and back. Bonding is of varied nature containing all human duty.

In Table 2 we have isolated the content of the symbols of space, movement or travel, and of bonding as they are represented in the above texts:

Table 2: Symbols of Space, Movement and Bonding

(1) The Seven Hills of Plovdiv |

(2) The Legend of the Rose |

(3) The Mason |

Places:

|

Places:

A Bulgarian master travelled to the kingdom of Abass shah and built for him a palace of unseen beauty. |

Places:

|

Travel:

|

Travel:

|

Travel: the master travels from place to place until he is bound by his art and love to death.

|

Bonding:

|

Bonding:

|

Bonding:

|

(3a) The Source of the White-Footed Maiden Places:

Travel:

Bonding:

|

||

(3b) The Bridge of Kadina Places:

Travel:

Bonding:

|

||

The reduction of this text to core symbols suggests that the mixture of real and fantastic elements in the travel legends under consideration affirms the existence of borders as natural limitations to human expression (bonding is seen as an expression of duty) while at the same time this legendary reality naturally expands to include geographical space within the larger area characterizing the experience of the legend's dramatis personae. Balkan legends of that nature could be used as cultural bridges, for power relations and confrontations are not the focus of the tale, but merely provide a three-dimensional background to the legendary projection.

In the third place, legendary action is built around the decision of the hero and thus gives the human individual pride of place.

All this allows building a set of archetypes and their further employment in the construction of e-space for legends where travel legends would hold a more important position serving as connections to culturally limited legendary spaces.

For the purpose of producing a legend-hypertext faster we have chosen to start from the hero who is the focus of all human narratives where the individual finds parallel experience, confirmation of values and actions, motifs for accepting or denying behavioural patterns as well as cultural motivation. The above texts contain core relations, which form oppositions representing generic and social attitudes.

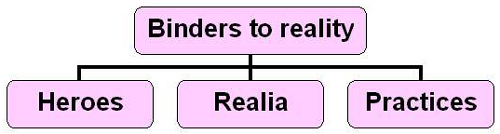

A second level in the archetypal set is the natural legendary environment: the space and places, as they are bound in legendary time (broader epoch) and in real historic time - the nearest time of the origin of the legend. Next come the artifacts or natural objects which bind the legend to the physical world. Legend as narration is set on action. Action provides a set of basic practices supporting the existence of the legendary dramatis personae and their world, i.e. our cultural roots.

The most important thing about building this multilevel set of archetypes is their physicality which would next allow attending to the multiple sites at which travel writing takes place (Duncan-Gregory 1999:4). In texts selected for discussion the set takes on the following appearance:

(1) The human individual: gender oppositions

(2) The dimensional features of legendary action:

(3) Binders to the physical reality

(4) Practices

E-ontology is also a liminal characteristics: it includes the attributes, functioning and connections within an e-space domain. As Christoph Kindle (2005) argues, ontologies as a way to describe a domain of interest will gain importance in the information retrieval area.

Legendary sets of archetypes can be easily translated as ‘archetypal attributes’ that can be adopted in e-space.

The nature of translegendary attributes suggests the cross-references that could bind archetypal attributes into an e-ontology:

Concrete sets of features in this case aim at making the unique accessible without translating it into a "concise and culture-free source document" or including it as a "culture-specific example" (Aykin 2002:7). Unlike technical writing, translegendary writing creates its own reality of infinite text and yet, unlike fantasy, it reaches the exits of e-space into the physical world. In this respect we side with Arnett who avers:

I look forward to future cross-cultural research efforts focusing on developmental comparisons within cultural contexts that attempt to combine, in part, the ethnographic approaches of the anthropologist, the psychological theories and methodologies of the psychologist, and the social policy concerns of the sociologist. (Arnett 2005:438)

The effects of introducing travel legends into the Internet space would, in a concentrated form, find expression in opening, in virtual reality, an exit to the physical world which, being laden with ethnic and cultural traits, suggests at the same time routes across cultures and dismantling of borders and demarcation lines between countries. We thus gain access to the fantasies of our shared human roots. By travelling through fantasy and in physical reality, legends provide a common space for folklore and trace its common cultural roots beyond current cultural diversity and contradictions. Making our way through a labyrinth of differences, we thus search for ethnic isles of culture and motivate their existence across borders and spaces.

© Gergana Apostolova (South Western University, Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Apostolova, G., The Self in the Net, IPSI-New York proceedings, 2006

Arnett, J.J., Adolescence in the 21 st Century, in Gielen, U.P., J. Roopnarine, eds., Cross-Cultural Perspectives and Applications , 2005

Aykin, N., Usability and Internationalization of Information Technology. ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Mahwah, NJ. 2005.

Dingwaney, A. (1995) ‘Introduction: translating "third world" cultures’, in A. Dingwaney and C. Maier (eds), Between Languages and Cultures: Translation and cross-cultural texts, Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press, pp. 3-15.

Dixon, R.M.W., Origin Legends and Linguistic Relationships in Oceania. Volume: 67. Issue: 2. 1996. pp. 127+.

Duncan, J., D. Gregory (eds), Writes of Passage: Reading Travel Writing, Routledge, London, 1999.

Holliday, A., M. Hyde, J. Kullman, Intercultural Communication: An Advanced Resource Book. Routledge. New York. 2004.

Iser, W. (1996) ‘Coda to the discussion’, in S. Budick and W. Iser (eds), The Translatability of Cultures: Figurations of the space between, Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, pp. 95-302.

Kindle, Ch., Ontology Supported Data Extraction and Evaluation, in IPSI-2005 Venice proceedings.

Kostova, L., Tales of the Periphery: The Balkans in the Nineteenth-Century British Writing, V. Turnovo: St. Cyril and St. Methodius UP, 1997.

Lévy, P., Cyberculture. Odile Jacob, Paris, 1997.

Malinowski, B. 1926. Myth in Primitive Psychology. New York: Norton.

Miller, J.H. (1996) ‘Border crossings, translating theory: Ruth’, in S. Budick and W. Iser (eds), The Translatability of Cultures: Figurations of the space between, Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, pp. 207-23.

Motzkin, G. (1996) ‘Memory and cultural translation’, in S. Budick and W. Iser (eds), The Translatability of Cultures: Figurations of the space between, Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, pp. 265-81.

Venuti, L. (1993) ‘Translation as cultural politics: regimes of domestication in English’, Textual Practice 7.2, pp. 208-23.

5.6. Border Zones: Travel, Fantasy and Representation

Sektionsgruppen | Section Groups | Groupes de sections

![]() Inhalt | Table of Contents | Contenu 16 Nr.

Inhalt | Table of Contents | Contenu 16 Nr.

For quotation purposes:

Gergana Apostolova (South Western University, Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria): TRANSLEGENDRY: Borders and Archetypes in Bulgarian Legends. In: TRANS.

Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften. No. 16/2005.

WWW: http://www.inst.at/trans/16Nr/05_6/apostolova16.htm